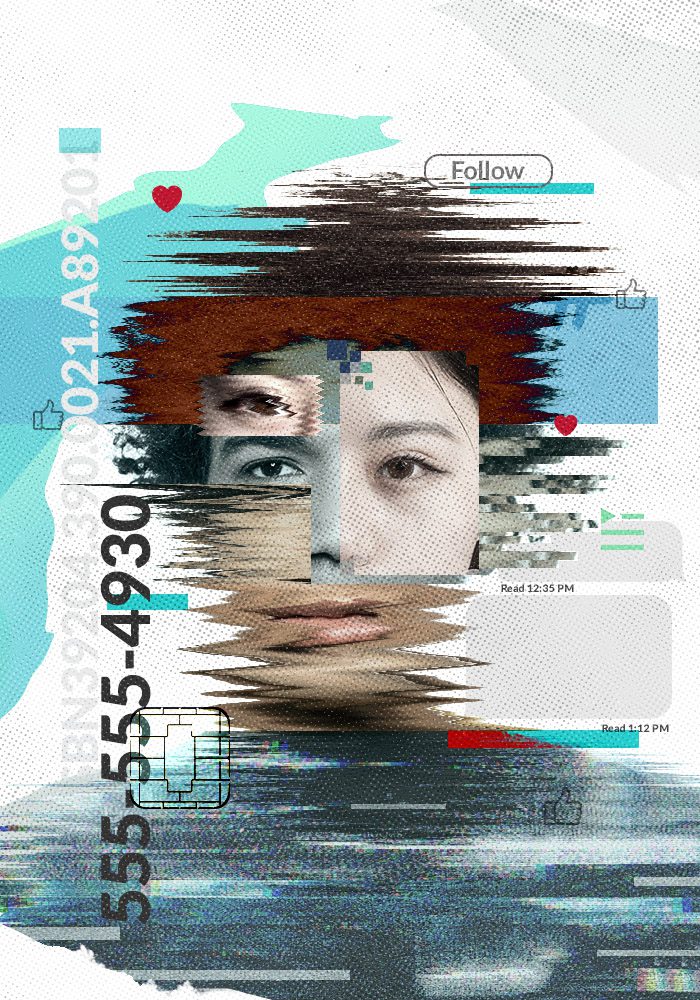

Who Controls Who You Are?

Your government wants to issue every citizen a digital ID.

Is this a good idea? Or a privacy nightmare?

Why worry about a digital ID when you’re walking around with a surveillance device in your pocket?

The phone you’re carrying around produces a steady stream of highly personal data about you. It’s a source of information far richer than an ID card, passport or other official document. And companies and governments want a piece of it. Read below to learn more about what the changing politics of digital identity means for you.

You’re a young office worker in America. When your alarm goes off at 6am, you do what most people do: you pick up your phone. You check your social media. You look at your calendar, fire off a couple of messages, roll out of bed, and hop in the shower. As you head out the door to work, you pop in your ear buds, open your favorite music-streaming service and turn up the Beyoncé.

Over the course of your day, you engage in hundreds of small interactions – each one meticulously tracked by your phone and stored in a faraway server farm. Your phone knows what route you took to work. It knows that you spent 15 minutes reading about politics and “liking” your friends’ weekend photos when you were supposed to be on a conference call. It knows who you were with when you hit that new after-work spot that everyone’s been talking about.

Each piece of data adds to vast digital dossier that is already hard for most people to comprehend, much less control. And it’s not just your phone – your car, your thermostat, your fitness tracker, and the checkout where you swipe your debit card on your morning coffee run are all sending information about you back to headquarters, where it can be aggregated and analyzed.

We’ve become so accustomed to sharing our digital lives, it almost seems mundane. But make no mistake: This is about power.

Imagine you’re a young office worker in China. You have a similar morning routine. But on your way to work, you stroll past a series of surveillance cameras equipped with facial recognition software. The cameras log your presence in a database that’s shared with a local police post. Just last week, officers arrested a man with an outstanding warrant after the cameras spotted him in a crowd. In a few short years, your government wants to integrate your town’s surveillance cameras into a system that will track a variety of online and offline activity, to reward people who engage in socially desirable behavior, and punish other people who do things the ruling Communist Party doesn’t like.

Historically, governments have kept tabs on their citizens using a handful of official markers: passports, birth and death certificates, social security numbers. In some countries, it’s a set of fingerprints on file with the secret police. When you can’t board a plane, open a bank account, take out a loan, or file for a tax refund without showing some form of government-sanctioned ID, that’s power.

Your digital identity – the sum of all the personal information companies and governments can access about you – is far richer and more personal than any paper document. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. In India, millions of poorer citizens who were never issued paper birth certificates are using government-issued IDs linked to their fingerprints and eye scans to access government benefits and open bank accounts. But in the wrong hands, and without the right checks and balances, digital identity can be a powerful weapon. Many Americans were troubled to learn that political operatives had used inappropriately obtained personal information to target millions of voters with political ads during the 2016 presidential race. In authoritarian countries that want to control restive populations or tamp down dissent, the stakes are even higher.

Here are some of the big questions facing governments, citizens, and companies as they grapple with this new and powerful form of identity:

Who owns your digital identity?

It’s your photograph. Your location. Your favorite song that you’ve had on repeat since you woke up this morning. The bits of information vacuumed up by the apps you rely on in your day-to-day life may not be part of your official identity, like a government ID number or an iris scan on file with the border patrol. But in some ways, they’re even more powerful. Companies or governments who can access enough of them can not only piece together who you are, they can gain valuable information about your political affiliations and consumer preferences. So, who owns your digital identity? And what rights does that ownership confer? The answer depends largely on where you live. In the US, corporations have typically controlled their users’ personal information. Many web sites’ terms of service state that when you open your account, you’re giving the company that runs it permission to collect your personal data – and profit from it. In Europe, regulators have attempted to correct what they see as an imbalance of power between consumers and big internet companies by giving people more control over their personal data (see next answer for how that works). Even China is also exploring policies that would require websites to seek user consent before using their personal information – although the government itself has wide latitude to snoop on citizens to protect public order and national security.

Should you have the right to be forgotten?

Let’s say five years ago you were arrested for a minor offense. The next day, your mugshot appeared on a local news website. You paid a fine and eventually forgot about it. But the internet didn’t. Now you’ve you’re about to apply for a new job, and your mugshot still appears at the top of a popular search engine’s results whenever someone types in your name. Should you have the right to request that your photo and search results be deleted? The European Union thinks so – its data protection rules include a “right to be forgotten” that allows people to ask websites to delete personal information that is outdated, or that they don’t want others to see. But where does the right to be forgotten cross the line into stifling free speech? What if the person demanding that a social media site take down embarrassing information is a politician running for national office? The EU rules allow websites to deny requests that would stifle free speech or otherwise go against the public interest. The issue of whether people should have control over their virtual identity isn’t always clear-cut.

Where should societies draw the line between privacy and security?

The information that people voluntarily give away about themselves online is just the beginning. In a growing number of cities around the world, just driving down the street or showing your face can result in your personal information being involuntarily scooped up by a computer. Chinese authorities have enthusiastically embraced facial recognition technology for public surveillance. Some cities have even been testing “gait recognition” software that can identify people based on how they walk. In the South Korean city of Songdo, a prototype “Smart City” near the bustling port of Incheon, a network of security cameras can read license plates to automatically alert the authorities when tax cheats park their cars. In Pakistan, Chinese companies are helping authorities build “Safe Cities” with surveillance cameras that can track people on watchlists. Such technologies have the potential to keep people safe from terrorists and other threats to public safety, but without the proper controls, they could also be easily turned against populations. How can citizens ensure that once these technologies are widespread, there are limits on what governments can do with the information they collect?

Video

Further Reading

1. The AI Cold War That Threatens Us All – An article about virtual identity, authoritarianism, and democracy in the context of artificial intelligence.

2. The Solace of Oblivion – An article about the right to be forgotten, tracing the history of the idea that people should have the right to request the deletion of digital information collected about them online

3. Your Apps Know Where You Were Last Night, and They’re Not Keeping It Secret – An investigation detailing the detailed location data collected, and in some cases sold, by the creators of smartphone apps.

This post is part of Digital Revolution: Technology, Power, & You. Funding for this project was generously provided by Harold J. Newman