Global Views of American Democracy

We are in the middle of what some are calling a “democracy recession” not just globally but in the United States as well. A recent Pew study found, in the United States, “46 percent of those aged 18 to 29 would prefer to be governed by experts” and a study by Mounk and Foa in the Journal of Democracy reported one quarter of American millennials agreed that “choosing leaders through free elections is unimportant.”

Statistics like these abound. Yale political scientist Tim Snyder argued that “it’s no surprise that millennials don’t support democracy” because they reasonably anticipate they will be worse off than their parents. Snyder pointed to growing economic insecurity and inequality – as well as new voter suppression laws – as sources of frustration with democracy. As Ian Bremmer has pointed out, the display of “hanging chads” and the electoral dysfunction of the 2000 election looms large in the minds of would-be democrats overseas. Instead of prodding foreign governments to be more democratic, the United States could focus on being a better exemplar of democracy. This project seeks to understand how we can model a democracy worthy of emulation, and develop a strategy of democracy attraction rather than democracy promotion.

View our reports from 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023 to see more work on this topic.

This annual survey is part of Independent America, a multi-year research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs.

Global Views of American Democracy: Implications for Coronavirus and Beyond

Map and Videos | Executive Summary | Introduction | Specific Findings | Conclusion | Methodology

Executive Summary

This report is being released as the global COVID-19 pandemic is threatening the physical and economic health of people across the world, and disrupting relations between countries. As political leaders narrow their focus on protecting their citizens, national solidarity could crowd out international cooperation. In moments like this – when people are tempted to shed curiosity and concern about, or even scapegoat, foreign publics – it is imperative to understand what the world thinks. As such, our annual survey of how people from different countries perceived the United States and its democracy is quite timely.

At the Eurasia Group Foundation, we believe that one of the most powerful ways to advance the cause of democracy abroad is to model its wisdom and promise at home. This includes demonstrating how America’s democratic government can carefully and capably respond to a crisis such as this one. The perceptions of America’s response will likely factor into next year’s report. In the meantime, this is the second year of our survey, and we review some of its most noteworthy findings here.

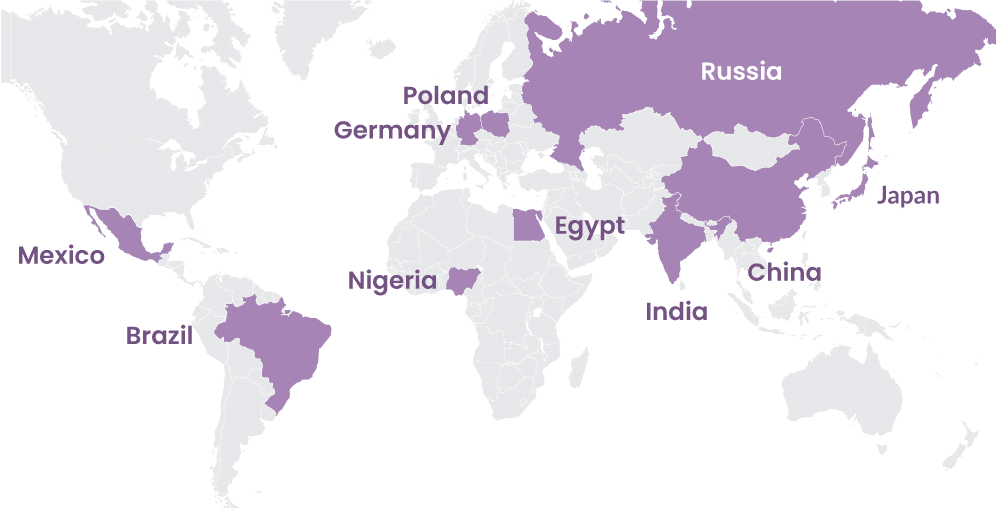

But first, we made a couple updates to this year’s survey. In addition to surveying people in Brazil, China, Egypt, Germany, India, Japan, Nigeria, and Poland, we also collected responses in Mexico and Russia. To account for China’s increasing international influence, we added questions to gauge people’s preference for either American or Chinese global leadership, and reasons for that preference.

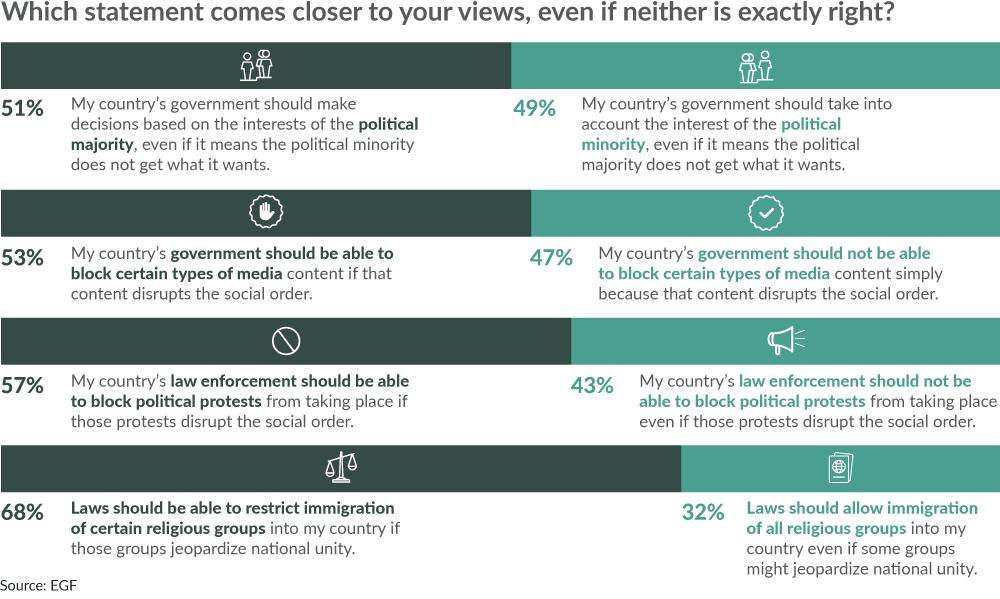

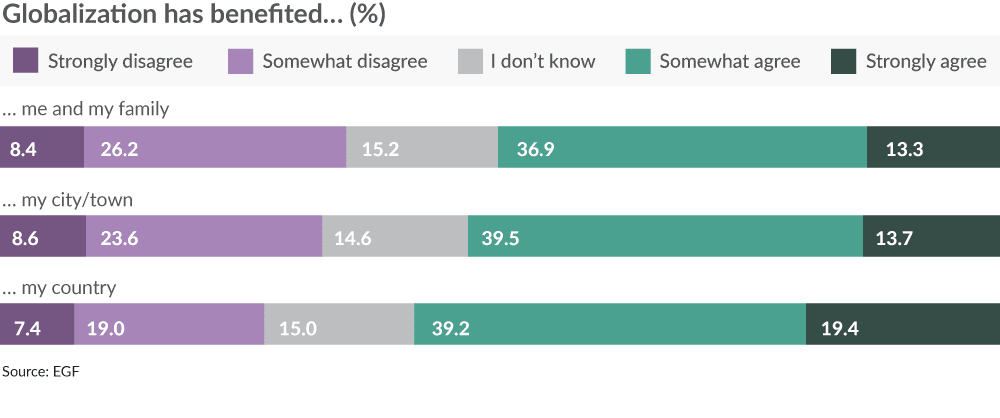

Fareed Zakaria presciently wrote an essay “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy” in Foreign Affairs in 1997, and since then, a wave of democratically elected leaders has claimed popular support as they suppress individual liberties in the name of stability and security. So we included a battery of questions to understand how liberal or illiberal people’s attitudes were around things like media censorship, the preferences of political minorities, political protest, and immigration of particular religious groups. Given that modern illiberalism is often viewed as a backlash against globalization, we also added questions measuring attitudes toward globalization.

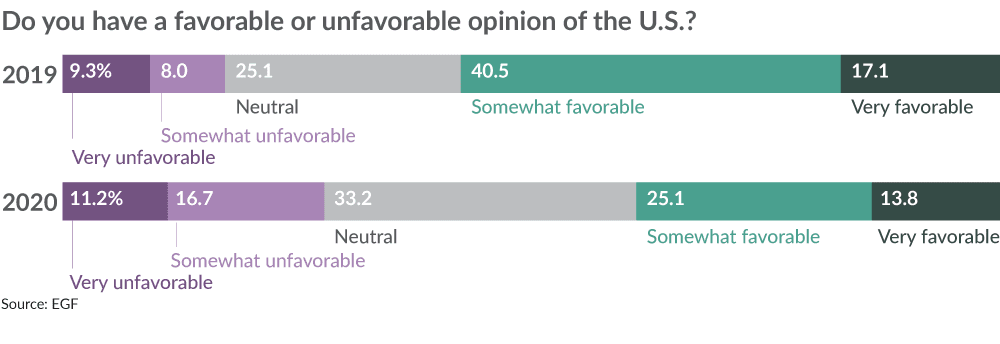

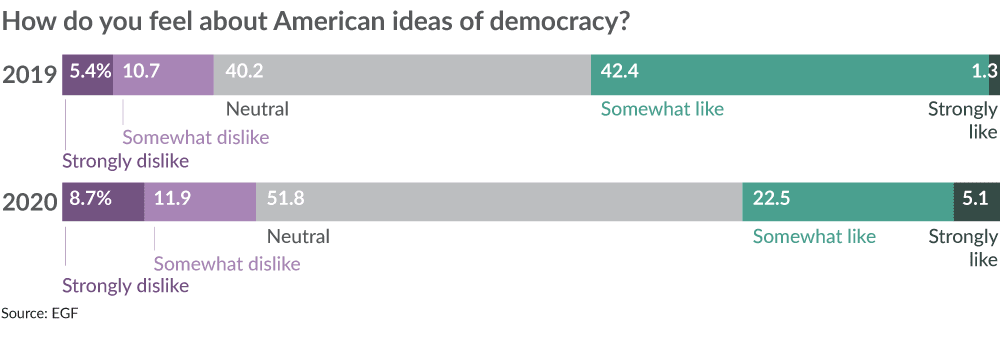

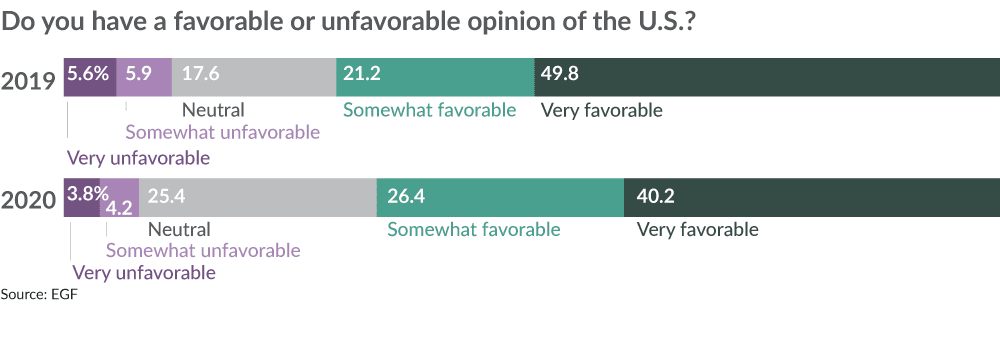

Between last year and this, we observed significant changes in views toward the U.S. and its form of government and political culture. The starkest declines came from China, where positive views of the U.S. decreased by 20% and positive views of American democracy decreased by 15%. We saw the sharpest increases in Egypt, where 11% more people hold positive views of the U.S., and about 20% more believe America’s democracy “sets a positive example for the world.”

As with last year, opposition to President Trump and resentment about America’s expansive foreign policy were the two most significant drivers of anti-American attitudes in the countries we polled. And having a friend or family member in the U.S. or consuming American cultural products positively influenced pro-American attitudes in most cases.

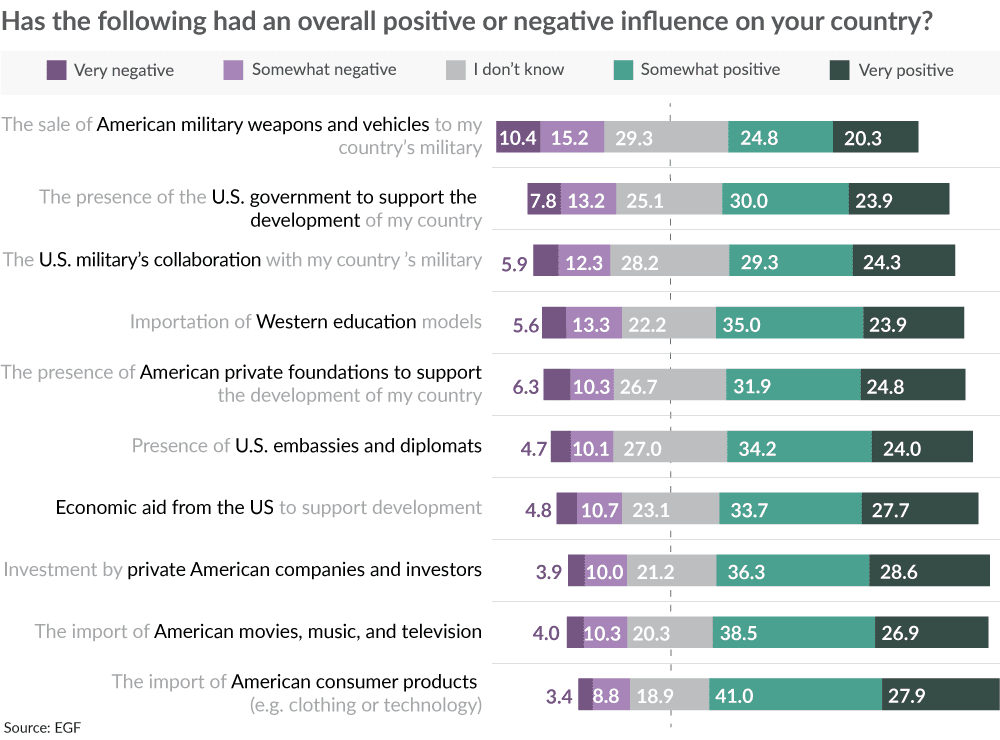

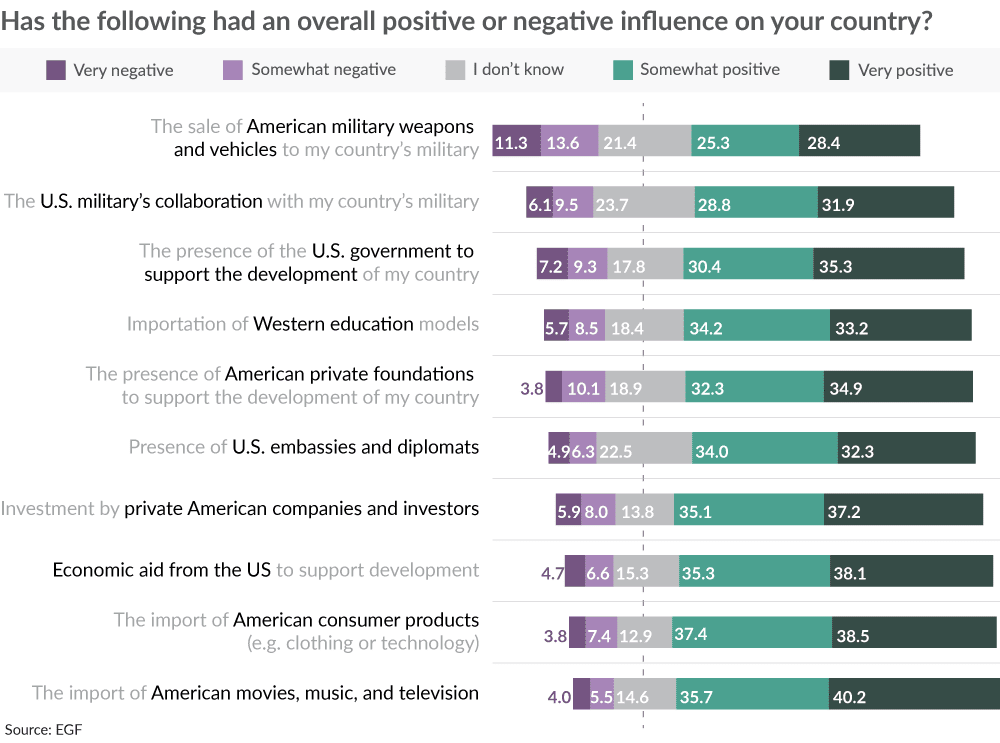

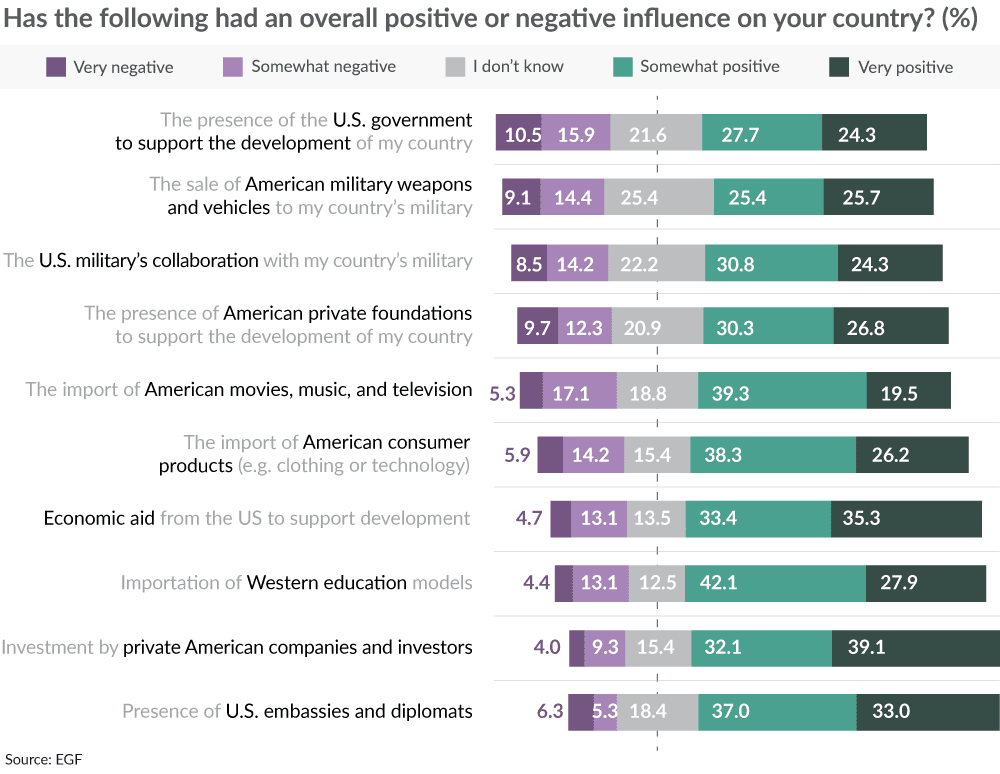

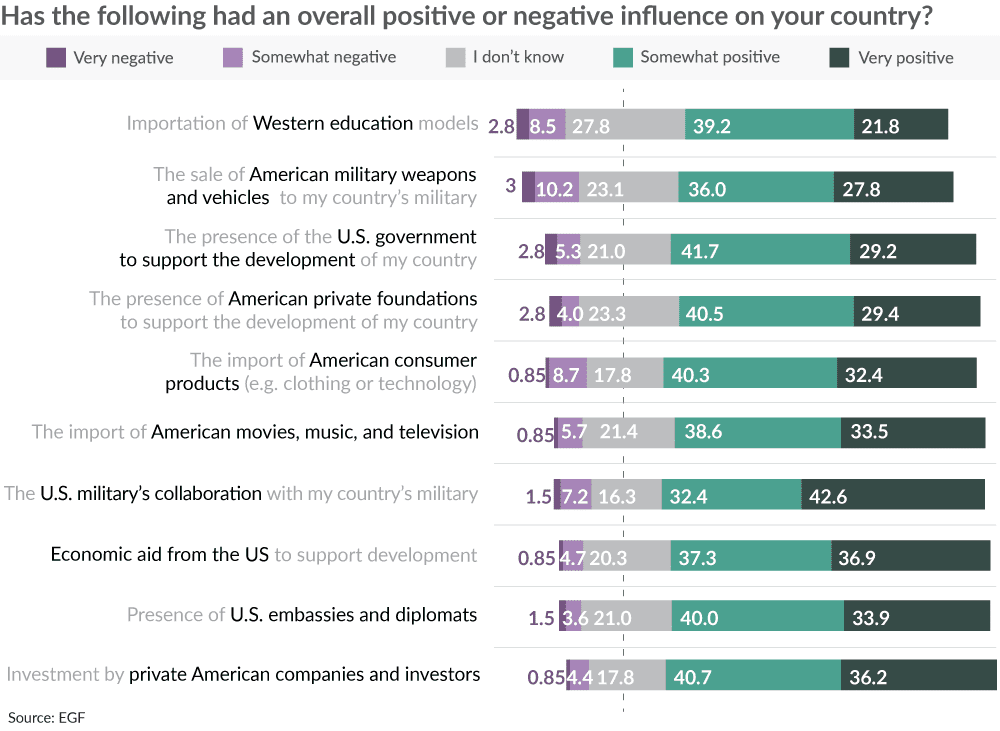

Another finding underscores how American interventionism sows anti-Americanism around the world, and how a more restrained U.S. foreign policy could do the opposite. In a list of ten different types of assistance or aid from the United States, the least popular internationally were the sale of military weapons and vehicles, development support from the U.S. government, and U.S. military collaboration.

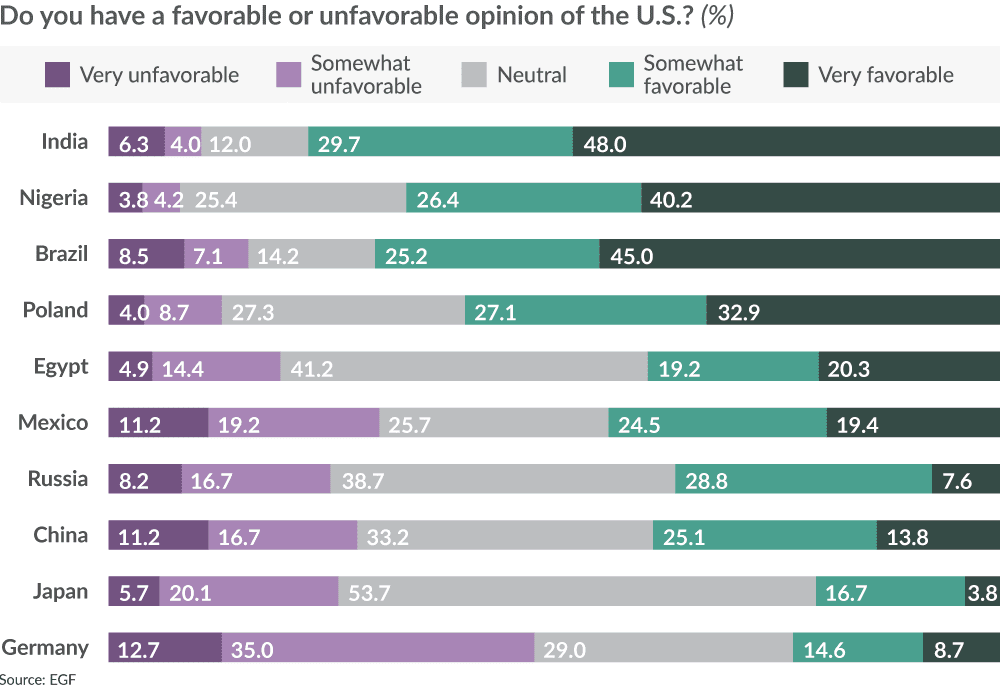

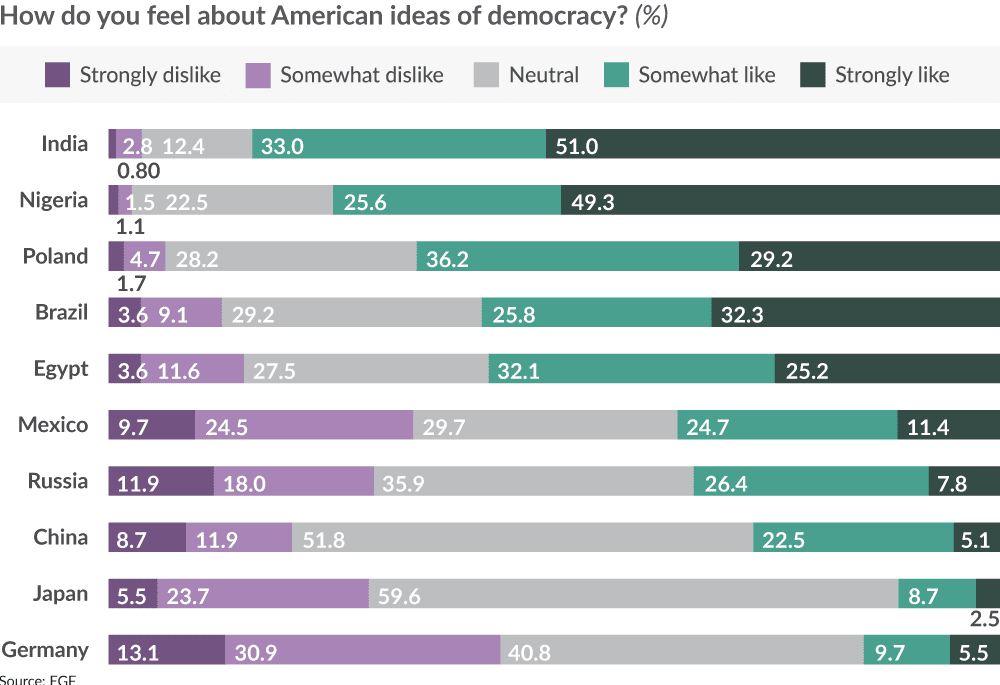

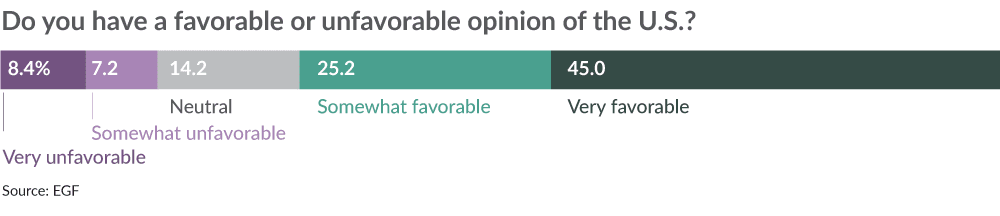

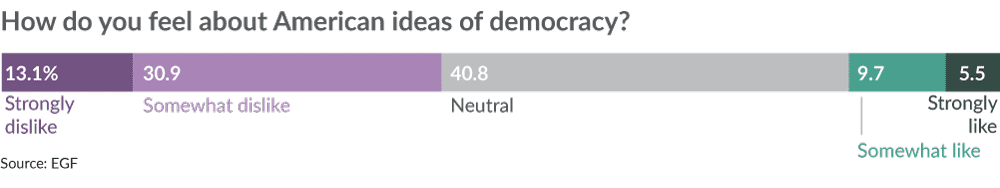

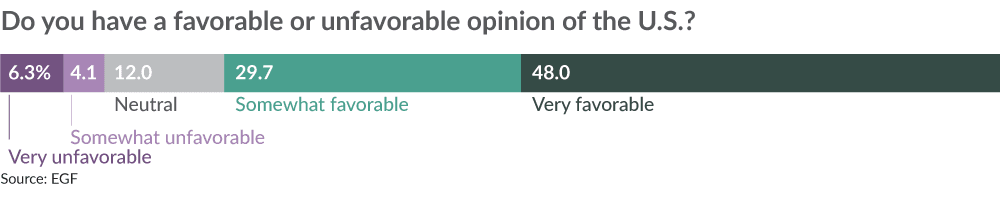

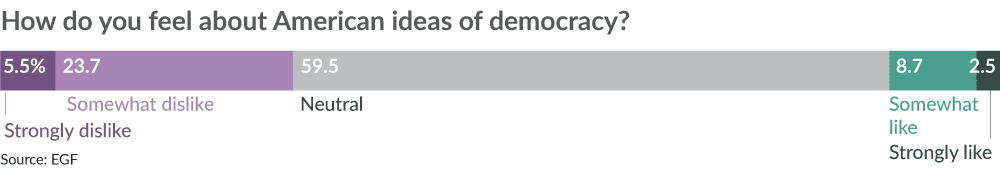

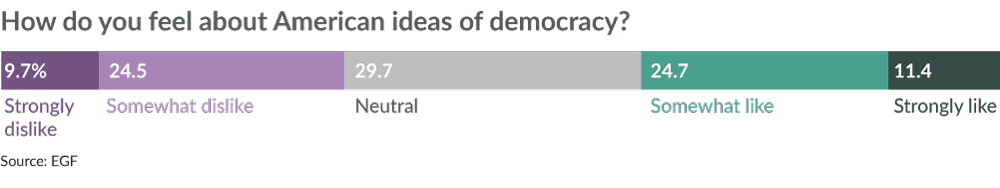

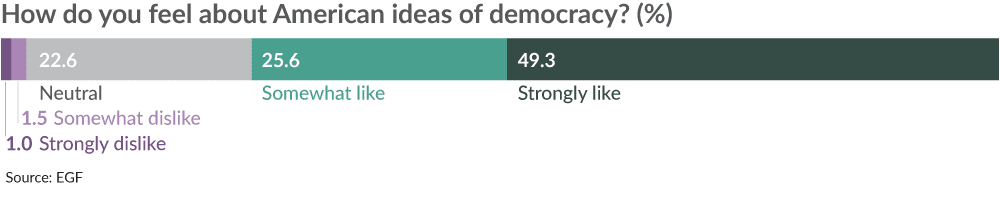

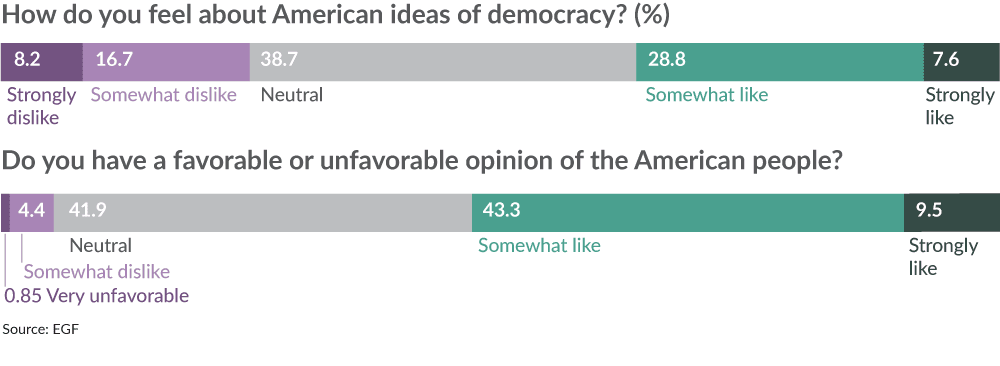

Generally, people across the world maintain a positive opinion of the United States and roughly twice as many like as dislike American ideas of democracy. However, over the past year, support for American-style democracy has dipped by 3% (in the eight countries we surveyed both years). It’s worth noting that the German and Japanese publics held less favorable views of both the United States and its democratic ideas than China, Russia, Mexico, and Egypt. Popular opposition to the U.S. could limit geopolitical action by the leaders of these two crucial American allies.

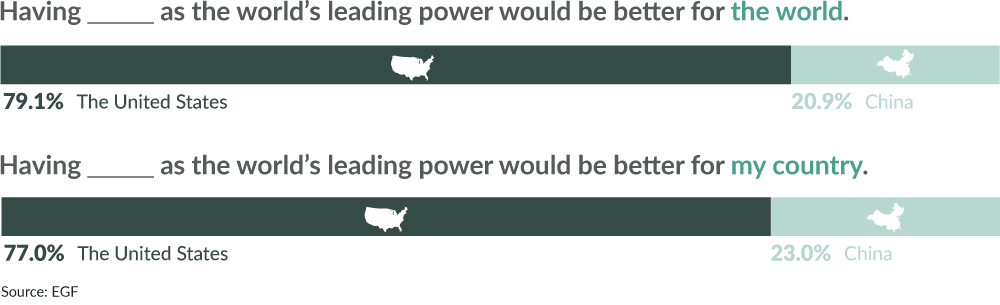

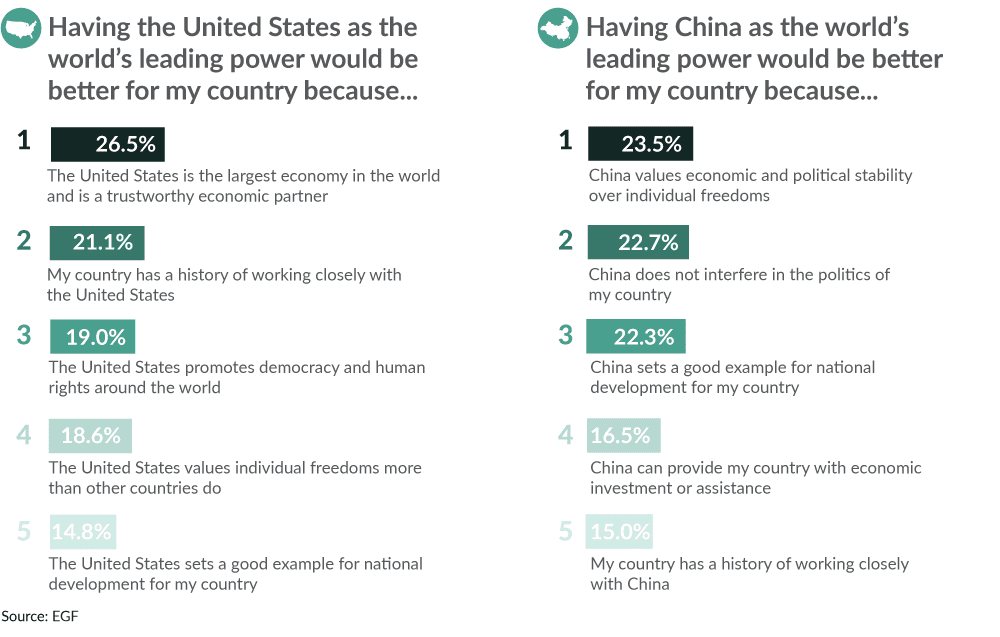

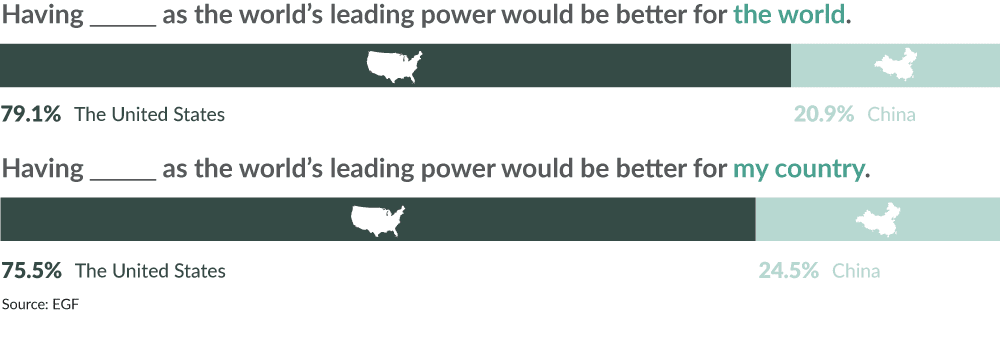

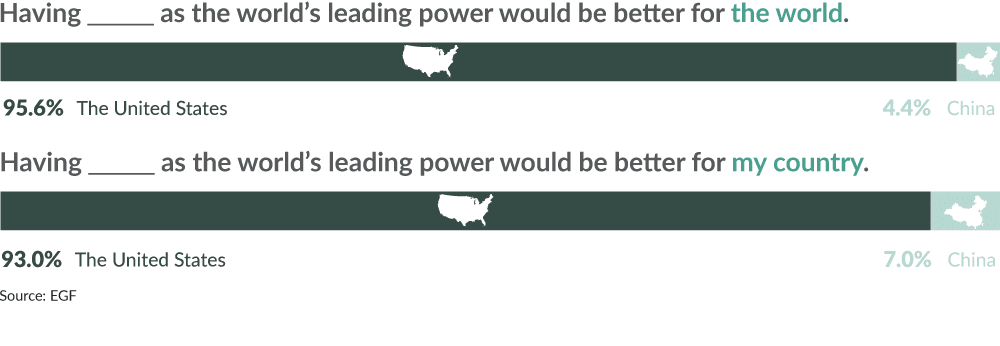

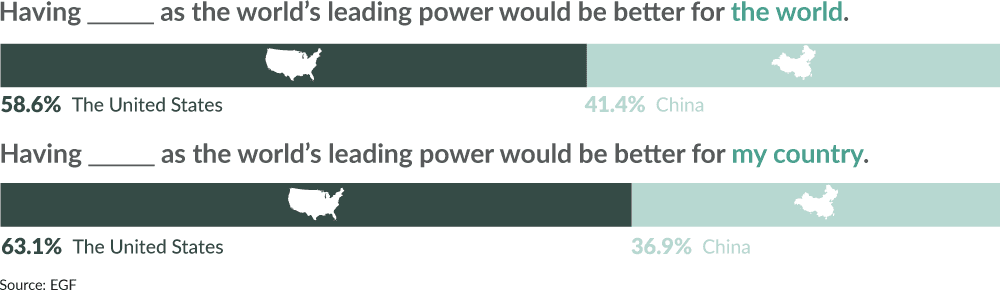

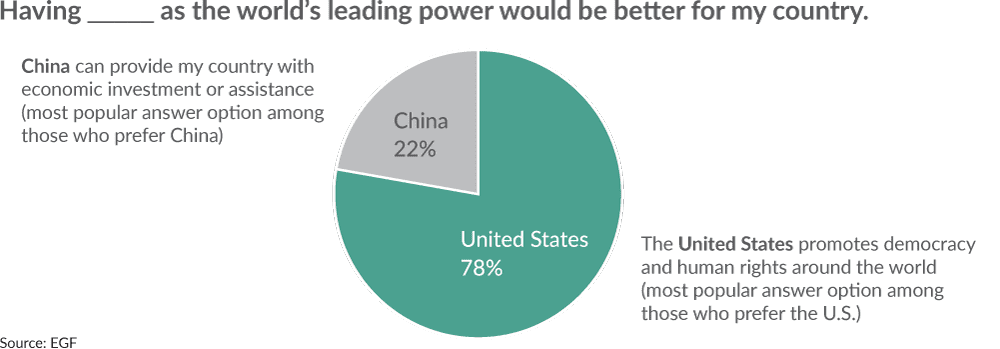

More than three-quarters of respondents across nine countries (we exempt China from this analysis) prefer the U.S. to China as “the world’s leading power.” This preference for U.S. leadership appears more transactional, however. The two most popular rationales describe economic partnership, and a history of working closely with the United States. Support for democracy, freedom, and human rights were less frequently cited. People who prefer China do so because it “values…stability over individual freedoms” and because it “does not interfere” in their country’s politics.

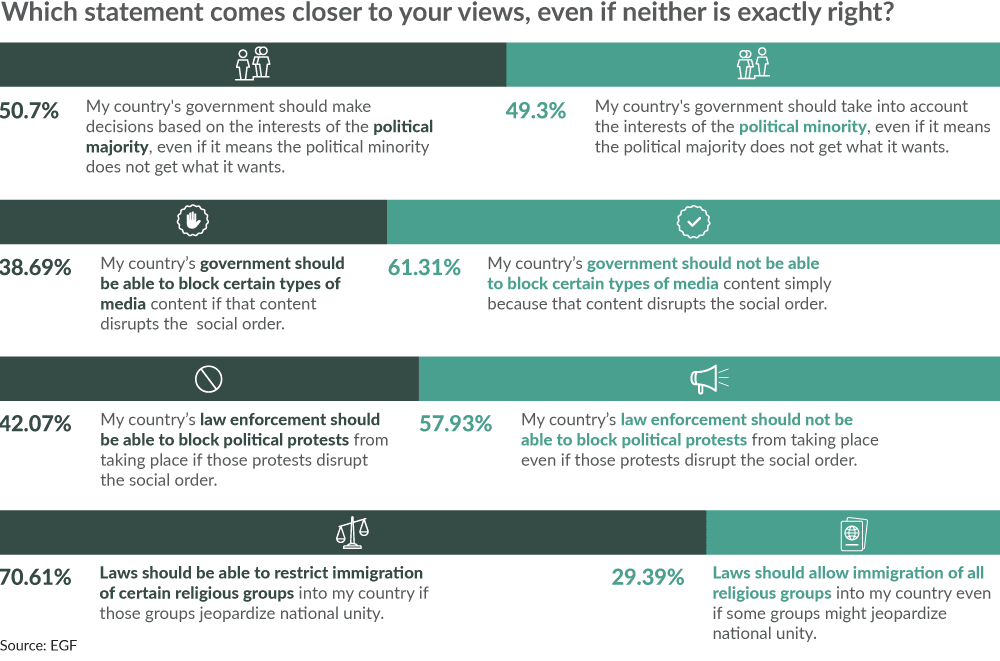

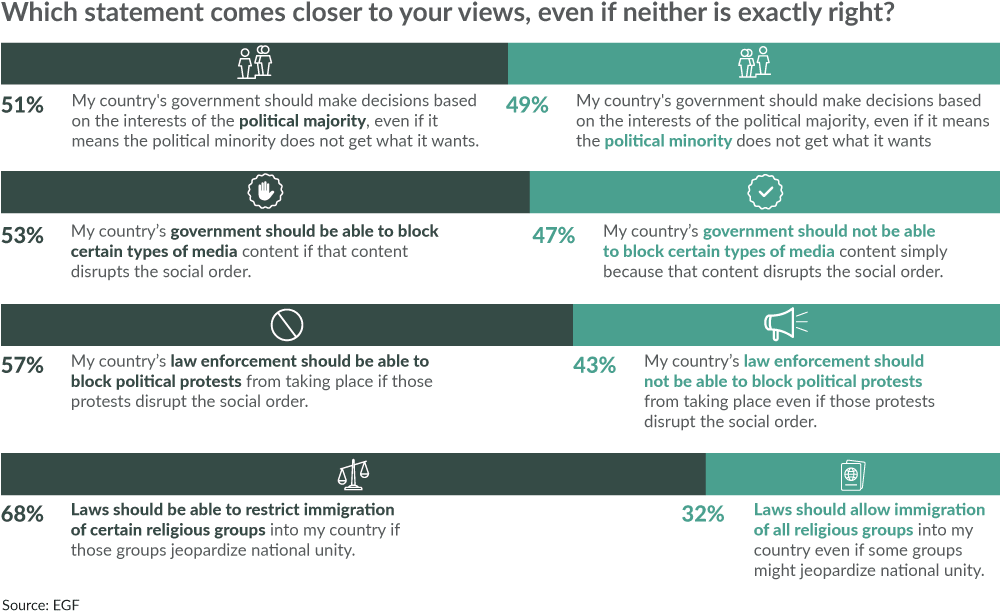

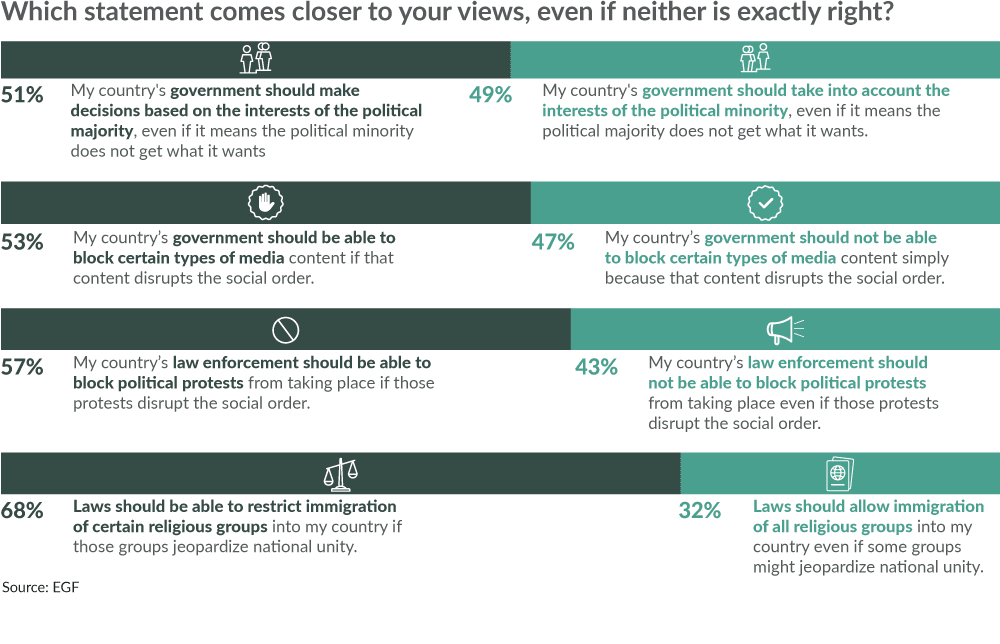

Finally, people in the ten countries we surveyed are most liberal when it comes to accounting for the views of political minorities even if it jeopardizes majority preferences. They are least liberal when it comes to allowing the immigration of all religious groups even at the cost of national unity. When it comes to freedoms which could potentially disrupt the social order, international opinion is more supportive of media freedom than the freedom to participate in a political protest. Nevertheless, at least a slim majority preferred the illiberal to the liberal option across all four of these political dilemmas.

From an analytical standpoint, “international opinion” is at best a gross generalization and at worst a downright abstraction. Every country’s views are idiosyncratic. Moreover, opinion differs within countries, not simply between them. Political science has a long tradition of using countries as units of comparison, and our use of them is admittedly expedient. With this disclaimer in place, turn to the Specific Findings section for a more detailed country-by-country analysis.

- Most Brazilians hold favorable opinions of the U.S.and American ideas of democracy. They also look upon U.S. foreign policy favorably, believing American soft power has had a positive influence. More Brazilians believe the U.S. has promoted stability in 2020 than in 2019, which coincides with their increased confidence in President Trump.

- Favorable opinions of the U.S. and of American democracy decreased markedly between 2019 and 2020 among Chinese respondents. Favorable opinions of the U.S. decreased by nearly 20% while unfavorable opinions increased by 11%. Positive views of American ideas of democracy decreased by 15%. Half of respondents believe U.S. influence has made the world a worse place.

- Egyptian opinion of the U.S. remains mixed, but favorable attitudes increased this year. Egyptians think the U.S. has the best form of government out of 15 countries, and two-thirds believe American democracy sets a positive example for the world. However, Egyptians are more skeptical of U.S. foreign policy in their region.

- Out of the ten countries surveyed Germans have the most negative view of the U.S., with 60% disliking American-style democracy. Negative views about America stem from dislike of President Trump, the belief that American democracy is hypocritical, and decreasing confidence in American’s global role. Germans generally value liberal attributes of democracy, though are more mixed on immigration policy.

- Over eighty percent of Indian hold positive opinions of American-style democracy. They have the most favorable views of the U.S. out of the ten countries surveyed. The primary rationale is that “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state.” The overwhelming majority of respondents believe external influences like globalization and U.S. foreign policy have positively impacted their country.

- Japanese respondents remain somewhat indifferent to the U.S. and its ideas of democracy, with only eleven percent liking those ideas. While the majority of Japanese are indifferent about the effect American foreign policy has on the world, nearly all respondents prefer a U.S.-led world order to one led by China.

- Mexicans do not have particularly favorable views of America, its democracy, or leadership. American-style democracy would be more popular if minority groups were treated more fairly, there was less corruption in politics, and the income gap between rich and poor was smaller. Most respondents believe U.S. military bases threaten Mexico’s independence. Nearly half would prefer a China-led world order.

- Nigerians are overwhelmingly pro-American. However, positive attitudes dipped between 2019 and 2020. They value American ideas of democracy, especially the protection of individual liberties and equal treatment by the state. Seventy-five percent of Nigerians believe American foreign influence is positive.

- Most Poles like U.S. democracy and highly value equality under the law and individual liberties; though positive views toward the U.S. decreased by eleven percent in the past year. Poles generally view the presence of the U.S. military in their region positively, and even more believe America has a responsibility to maintain global stability. Like Germany, a strong majority favors restricting immigration.

- Only about one-third of Russians hold a favorable opinion of the U.S. American foreign policy likely explains why: a majority believes U.S. influence – including development aid and Western education models – has made the world a worse place. When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive, the most popular answer choice was if U.S. foreign policy was more restrained.

Introduction

The United States has long styled itself as the leader of the free world, boasting a form of government worthy of emulation, a stabilizing military and economic presence, and universally appealing values. This self-image animates much of the country’s foreign policy thinking. In some cases, America has earned this high regard. But in the past two decades, the geopolitical supremacy of the United States has taken a hit. What pundits call the American-led rules-based international order is being challenged by individuals and movements, both foreign and domestic, which openly question its wisdom and challenge its legitimacy. In short, American-style democracy finds itself at a tenuous moment. Institutions prove brittle, as liberal internationalism is thwarted by illiberal nationalism.

At the Eurasia Group Foundation we seek to understand what people around the world think and feel and believe about the United States and its political ideals. Our basic premise is that public opinion matters when contemplating foreign policy. This might seem obvious. Democratic government runs on the consent of the governed, and even a nondemocratic government requires the public perception of political legitimacy. But this deviates from some political science traditions which consider institutions and structural variables as more consequential and, therefore, more suitable for investigation. But as democracy trudges through this precarious time – when its appeal is being questioned by a new wave of autocratic leaders, reactionary movements, and people disillusioned with the promise of freedom and democracy from the American-led world order – we thought it worthwhile to explore the most popular – and least popular – aspects of American democracy internationally, and how those opinions drive support or opposition to the U.S. more generally.

This is a crucial moment for democracy. The COVID-19 pandemic introduces new questions about governments’ responsibilities and international norms. Leaders try to protect their populations while respecting freedoms once taken for granted. China’s draconian restrictions are credited for “flattening the curve” of new infections and dramatically decreasing that country’s death rate. One American journalist writes:

Barely more than two decades ago, the United States saw itself as a kind of eternal and all-powerful empire — the indispensable nation. It would have seemed laughable, then, to be told that China would have produced a far better and more comprehensive pandemic response — a shamefully superior response. 1

That journalist laments how American leadership suffers when countries now turn to China, which sends them “a huge supply of necessary equipment and human resources.” As the U.S. extracts itself from unsuccessful wars and continues to spend a fortune on its military, the country’s reputation as a stabilizing presence is more acutely called into question. Military power is ultimately impotent against the virus. America’s military dominance stirs resentment in certain countries, and China’s soft power rises while America’s falls.

A recent survey by a leading global PR firm found Americans less confident in their country’s preparedness for the viral outbreak than Canadians, Germans, Brits, South Koreans, and even Italians.2 And an (albeit unscientific) online Twitter poll by EGF’s board president Ian Bremmer pointedly asked, “who is doing the best job responding to the coronavirus crisis?” Of roughly 34,000 responses, people chose China over the U.S. by a nearly 4-to-1 margin.3

To be sure, the international survey upon which this report is based was fielded – and our data collected – before the COVID-19 pandemic was frontpage news (February 15 – March 3, 2020). Our questions dealt with a series of national security and foreign policy topics and general impressions of American-style democracy generally, but they did not address actual or hypothetical public health topics or pandemic preparedness and response. However, given the rise of China’s geopolitical influence in Asia and throughout the world, we did add several new questions this year which measures opinion about China’s international leadership relative to that of the U.S. We also asked new questions to compare the support for specific freedoms – related to the press, political protests, immigration, and religious and political minorities – across different countries.

Like last year, we discovered that America’s soft power is a strong source of pro-American sentiment around the world. People who have traveled to the U.S., have friends and family members that live in the U.S., and/or consume American cultural products like music and movies are significantly more likely to have a favorable opinion of the U.S. Also like last year, dislike of the current American president or of America’s interventionist foreign policy are two of the most potent drivers of unfavorable opinion.

But this year’s report makes new discoveries. This is partly because we cast a wider net. We increased the number of countries surveyed from eight last year to ten this year. Russia and Mexico are the new additions. And we increased the worldwide sample from 3,277 to 5,249. In certain cases we’re able to make year-to-year comparisons. Our goal over the longer term is to accumulate longitudinal data to help us analyze how people’s views of America and its style of democracy change over time.

As you read the following pages, you’ll see the United States continues to be held in high esteem by many people around the world. Though support for the U.S. has wavered in some countries, and the popularity of democracy is highest in some countries with the least experience of it, this is a moment for reflection, not despair. By seeing themselves through the eyes of people in ten politically and culturally diverse countries around the globe, Americans can achieve a new level of self-scrutiny which can inform necessary changes in practices and policies to restore the power of America’s example.

Specific Findings

Brazil | China | Egypt | Germany | India Japan | Mexico | Nigeria | Poland | Russia

International Trends

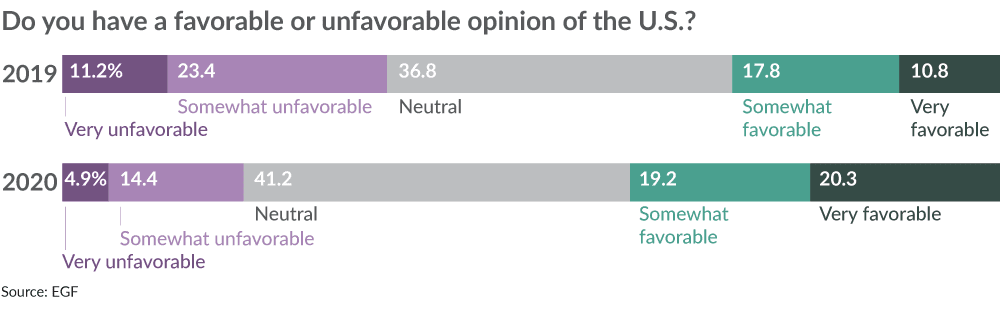

The international popularity of the United States held steady in the past year. Roughly half of our respondents had a favorable opinion of the U.S., with 29% neutral and 22% holding an unfavorable opinion. There are two notable exceptions: positive views of the U.S. decreased by nearly 20% in China, and increased by roughly 11% in Egypt.

We wanted to know what types of opinions or experiences contributed to positive or negative views of the U.S. So we looked for a relationship between certain soft power variables and noticed that people who had lived in or traveled to the U.S. were most likely to have a favorable opinion of the country, followed in order by people who had a connection to their country’s diaspora (i.e., friends or family members living in the U.S.), and those who have consumed American cultural products (i.e., movies, music, or news).

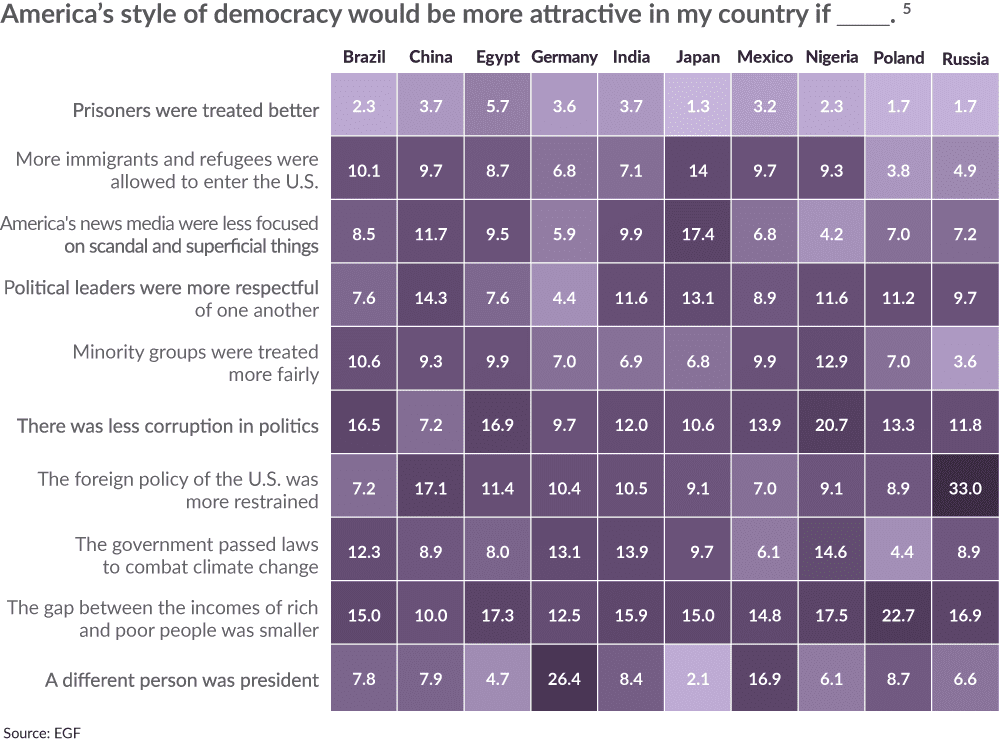

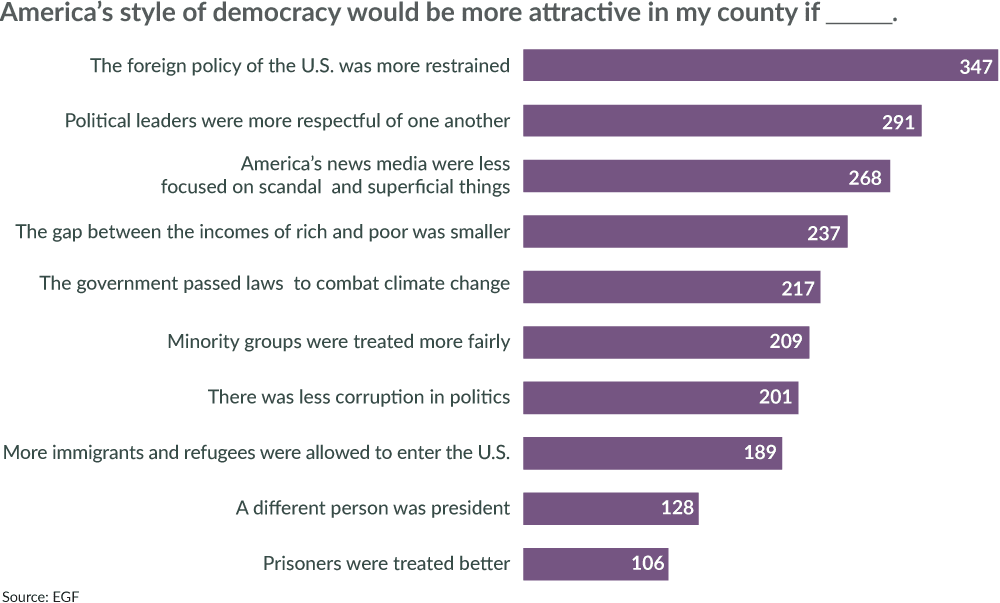

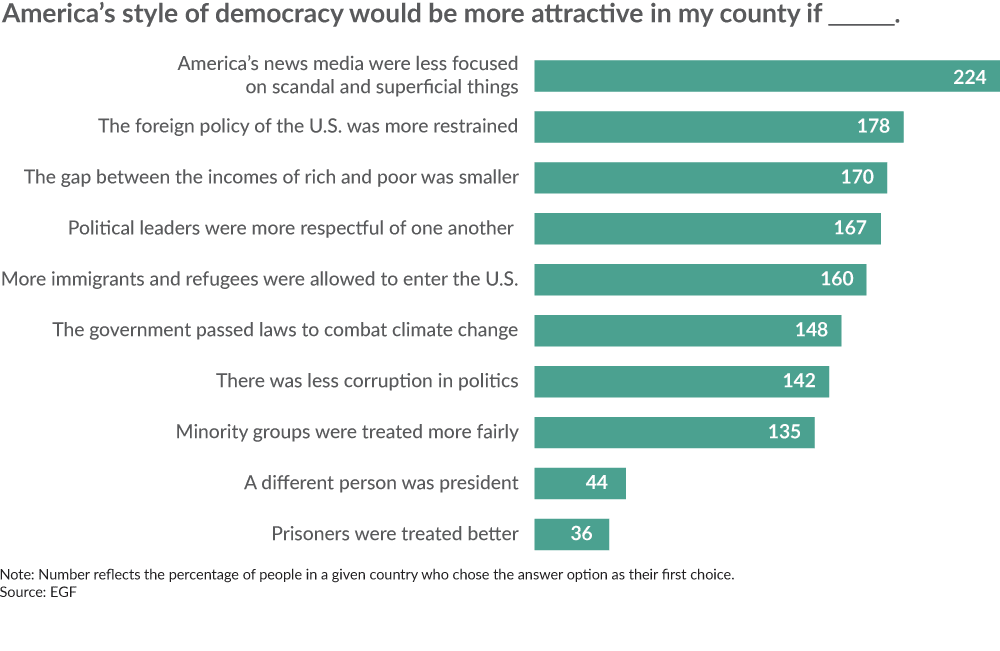

Similarly, we sought to understand how perceptions of American democracy’s shortcomings related to favorability of the country overall. We asked respondents what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive and provided ten answer options. The two most frequent answers for those with unfavorable opinions of the U.S. were: “a different person was president” and “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained.”4 This is mostly consistent with our results from last year, though perceptions of “the gap between the…rich and poor” was also a significant driver then.

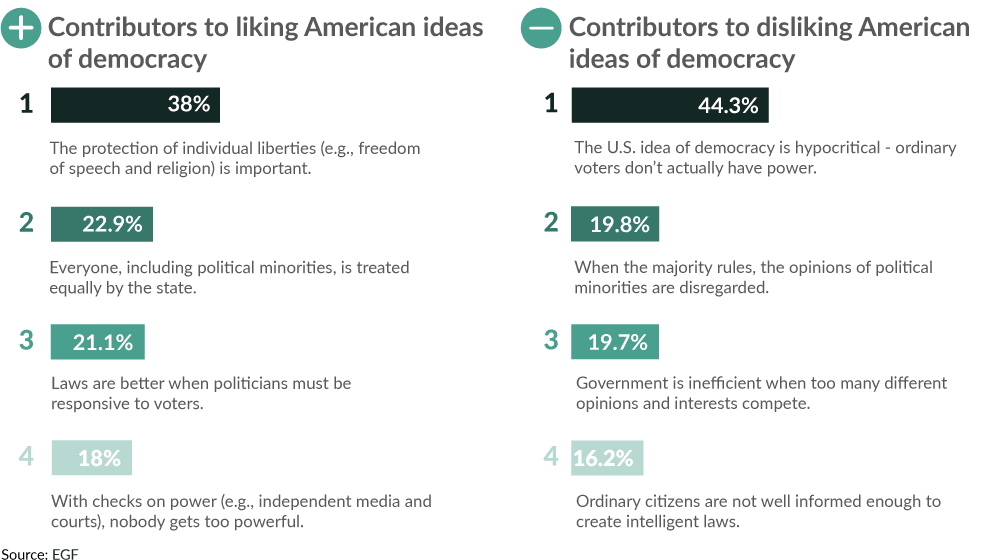

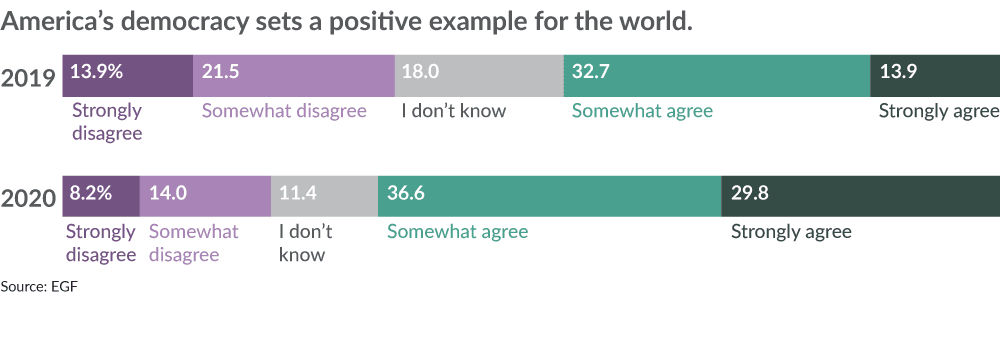

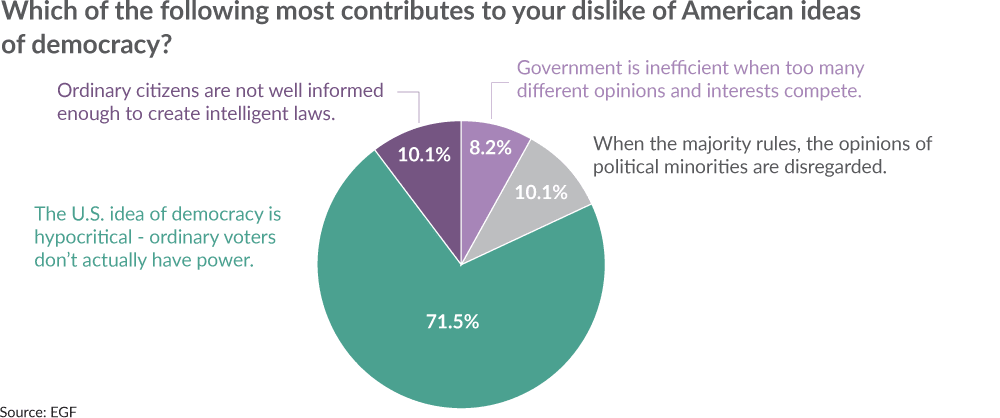

Internationally, support for American ideas of democracy appears to have softened in the past year. In the eight countries we surveyed both years, 3% fewer people claim to like these ideas. Nevertheless, as with last year, more than twice as many people report liking as they do disliking them. American ideas of democracy are generally more popular in countries which have less experience of democratic government. Among a set of possible reasons provided, the top one for liking American ideas of democracy is the protection of individual liberties. The top one for disliking them is that they’re hypocritical since “ordinary voters don’t actually have power.”

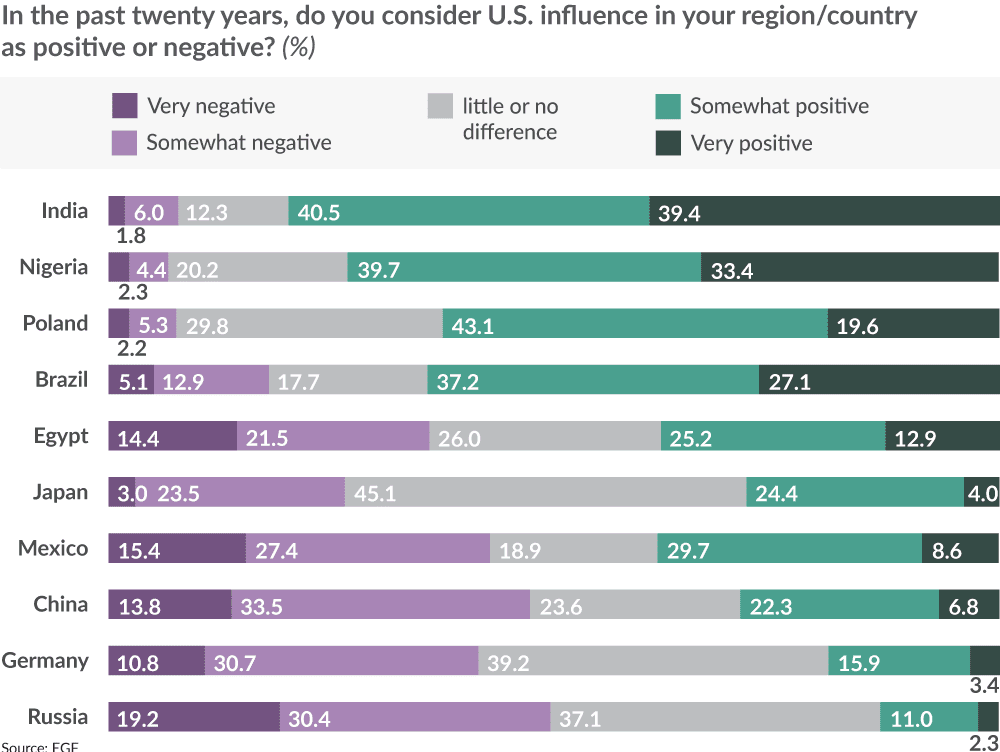

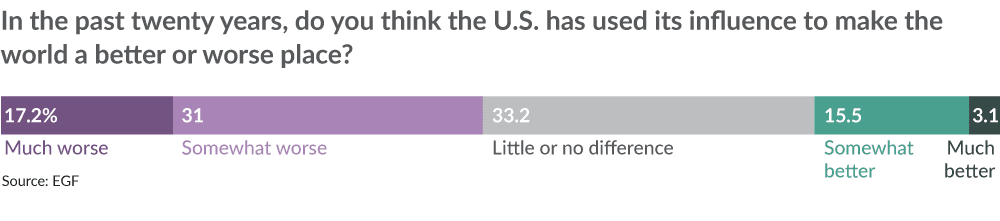

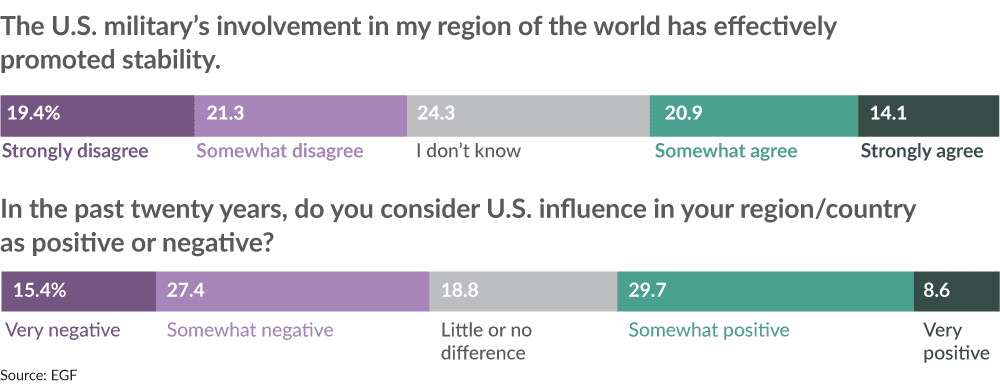

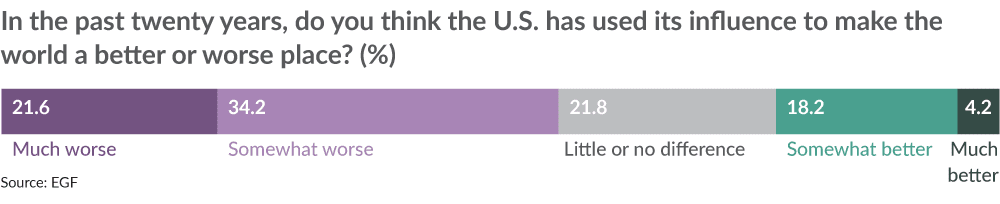

We also wanted to know what people across the world thought about the recent impact of American leadership and influence. Nearly half of the people in our ten countries believe the U.S. has had a positive influence in their region during the past twenty years. Three-in-ten have a neutral opinion while 22% believe its influence has been negative. These numbers are inverted for China and Russia, where nearly half the public believes U.S. influence has been negative. Interestingly, by more than two-to-one, Germans believe American influence in their region has been negative instead of positive. Among the most middling responses on the impact of U.S. influence are Mexicans, Egyptians, and the Japanese.

Given that globalization has become synonymous with Americanization in the minds of many, it’s predictable that respondents from the countries which had a negative appraisal of U.S. influence also gave low marks to globalization. People from Russia, Mexico, Germany, Egypt, and China are, respectively, the most likely to believe globalization has not benefited their family, municipality, or country.

Nevertheless, U.S. leadership is preferable to Chinese leadership for majorities in all the countries we surveyed except China and Russia. Russians were mostly likely to choose noninterference in the politics of Russia as the reason for preferring Chinese leadership, and least likely to choose the economic investment or assistance which China could provide. Nearly 80% of respondents outside China thought American global leadership was better than Chinese global leadership for the world and for their country.

But when asked why they preferred U.S. leadership, reasons related to economic or national self-interest overshadowed the appeal of American values. Internationally, the most popular reasons were that “the U.S. is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner” and that “my country has a history of working closely with the U.S.” These were followed by: “the U.S. promotes democracy and human rights around the world,” “the U.S. values individual freedoms more than other countries do,” and lastly, “the U.S. sets a good example for national development for my country.”

People across the ten countries we polled registered a preference for democratic governments. Asked to rank the top three countries with the best form of government, the most popular were: the U.S., Germany, the UK, Canada, Japan, and France. Only after came China and then Russia.6

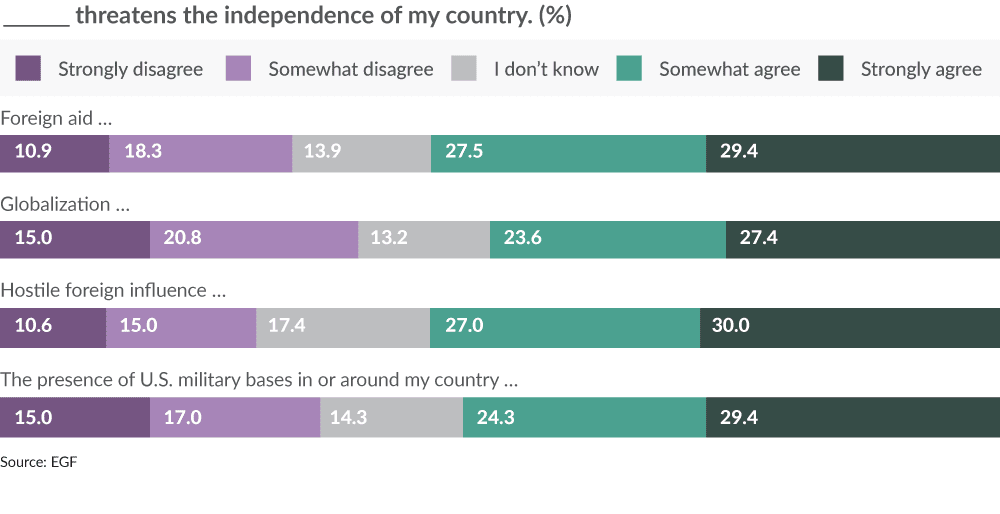

Despite these preferences, certain liberal democratic values outweighed others. Democracies always need to balance rule by political majorities with the protection of political minorities. So it’s not surprising our respondents were split down the middle when forced to choose whether their government should make decisions based on the majority’s interests or account for the minority’s interests. But when it came to political protests and immigration of certain religious groups, most people opted for social order and national unity over more liberal positions per the graphic below.

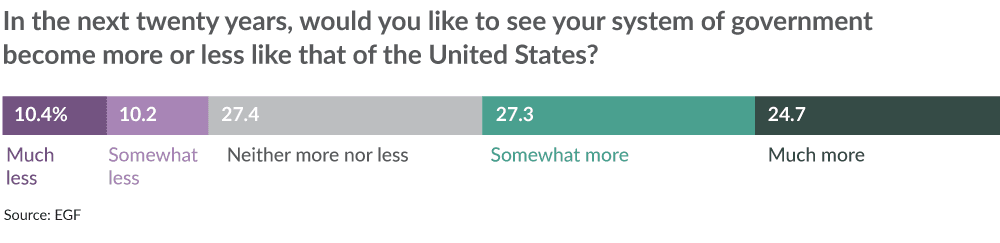

We’ve examined how people around the world view the United States and its style of democracy, what they think of America’s international leadership, which governments they most admire, and how they want their own government to negotiate certain liberties. We now end with a short review of whether, according to our data, people ultimately want their system of government to be more like that of the U.S. (52%) or less like that of the U.S. (21%, with 27% neutral).

We inspected the survey results to find what may have contributed to these attitudes. People who believe America’s democracy sets a positive example for the world were significantly more likely to want their government to be more like that of the U.S., and those who believed the U.S. should focus on the flaws in its own political system were significantly more likely to want it to be less like that of the U.S. But another more interesting relationship emerged from our data. We explored the possibility of a relationship between respondents’ support for their government being more like that of the U.S. and their appraisal of which component of democracy was best demonstrated by the U.S. Those who chose “respect for individual and civil liberties” were significantly more likely to want their government to be like that of the U.S.

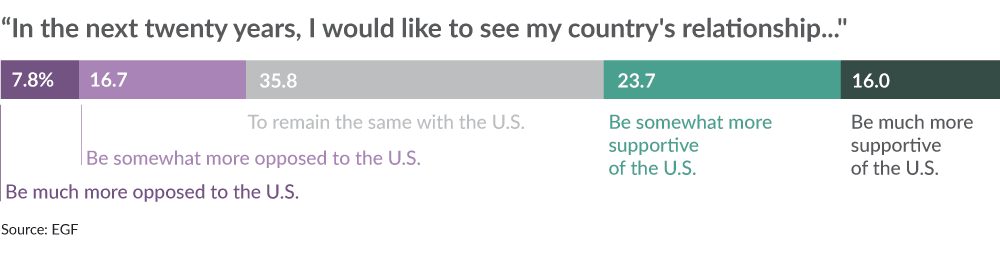

Finally, we asked people in these ten countries whether they’d like to see their country become more supportive or opposed to the U.S. in the next twenty years. Forty percent chose somewhat more or much more supportive while 24% chose somewhat more or much more opposed. People who believe “the presence of U.S. military bases in or around my country threatens” their country’s independence were more likely to desire a more adversarial stance toward the U.S.

Country-specific research

The majority of Brazilians hold favorable opinions of the U.S. (70% including 45% who have a “very favorable” view). Over half of all Brazilians either somewhat like or strongly like American ideas of democracy. While the number of people who dislike American ideas of democracy is very low (around 12%), the main reason why is: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” Among people who view American ideas of democracy favorably, the most popular reason they gave was: “laws are better when politicians must be responsive to voters.” Around 75% of respondents believe their government should be more, rather than less, like that of the U.S.

Probing further into what would make American-style democracy more attractive to people in Brazil, the most popular answer choices were: tackling income inequality, corruption, minority rights, and climate change. This might be explained, as discussed in last year’s report, by a desire for these same challenges to be tackled by Brazil itself. It may reflect what Brazilians see as problems in their own country.7

Respondents in Brazil generally look approvingly upon American influence and foreign policy. When asked if U.S. influence has made the world a better or worse place in the past twenty years, more than half chose somewhat better or much better. Similarly, the majority of Brazilians believe U.S. influence in and around Brazil has also been positive. And, around 75% of Brazilians somewhat agree or strongly agree that globalization has benefited them, their town, and country overall.

However, not all types of American influence in Brazil are given equal weight. Given America’s legacy of CIA-backed coups in South America,8 we weren’t terribly surprised that Brazilian opinion of U.S. military influence is less positive than views toward American soft power.

Nevertheless, the number of Brazilians who believe the U.S. has effectively promoted stability around the world increased between 2019 and 2020. This could be attributed to the rise of the ideological right in Brazil, whose confidence in U.S. President Donald Trump has increased, as reported by a 2019 Pew Global Attitudes & Trends survey.9

Around 75% of Brazilians surveyed believe having the U.S., rather than China, as the world’s superpower would be better for their country. The most popular rationales for choosing the U.S. were: “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner” and “my country has a history of working closely with the United States.”

Despite President Jair Bolsonaro’s recent crackdowns on freedom of speech and other civil liberties in Brazil, or perhaps because of them, most Brazilians believe the police should not be allowed to block political protests from taking place even if those protests disrupt the social order (although a majority of Brazilians also believe that the government should be able to block certain types of media content and restrict immigration of certain religious groups if either threaten national unity or the social order).

In last year’s report, our findings indicated the Chinese public had a generally favorable view of the U.S. and its form of government. This year, those numbers decreased significantly.

Between 2019 and 2020, favorable opinions of the U.S. decreased by nearly 20% while unfavorable opinions increased by 11%. In 2019, around 40% of Chinese respondents reported they either somewhat like or strongly like American ideas of democracy, and around 40% had neutral views. In 2020, positive views of American ideas of democracy decreased by 15%. When asked to choose a rationale for why people dislike American ideas of democracy, the majority of respondents were split evenly between the explanations that “government is inefficient when too many different opinions and interests compete” (31.5%) and “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power” (31.5%).

Chinese respondents appear ambivalent when asked whether they want to see their system of government become more or less like that of the U.S. Nearly half of respondents believe the Chinese government should be neither more nor less like that of the U.S. government, with the remainder evenly split between wanting their government to be less or more like that of the U.S. This finding represents a distinct shift from last year’s results, where a majority of people in China did want their government to be either somewhat more or much more like that of the U.S. (54%). And it’s not just with respect to American governance: positive views about the American people went down slightly (and negative views increased slightly) in 2020.

To be sure, Chinese respondents still value the same democratic attributes that people in other countries strongly value. The components of democracy that the Chinese view as being very important are: equality under the law and the protection of individual and civil liberties.

So our findings suggest that attributes of democracy are viewed somewhat positively by people in China; but not as positively when associated with the U.S. America’s foreign policy might explain why. When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive in China, the most popular answer was “if the foreign policy of the United States was more restrained.” This makes sense given escalating geopolitical and trade tensions between Washington and Beijing.

About half of Chinese respondents believed that in the past twenty years, U.S. influence has made the world a worse place, while 30% believe it has made it a better place. The Chinese view the presence of U.S. embassies and diplomats negatively, which makes sense in light of the recent crackdown on American journalists and diplomats in China.10 The type of American influence viewed most positively is economic aid from the U.S. and the import of American consumer products. And, as with American economic influence, a majority of people in China believe globalization benefits them, their family, municipality, and country.

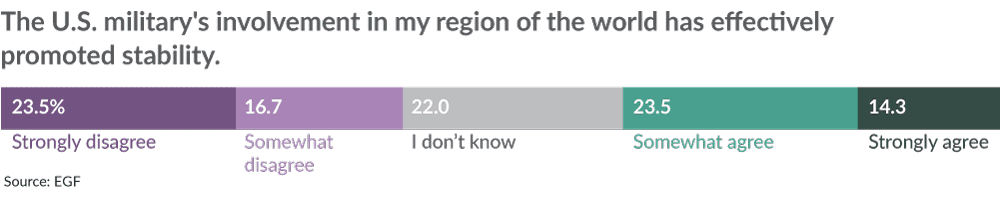

Further, slightly more than half the respondents in China believe the U.S. military’s involvement in their region of the world has not promoted stability. This is not surprising given their desire for a more restrained U.S. foreign policy, and other actions by Washington which Beijing deems antagonistic – such as the recent approval of the sale of $2 billion in military equipment to Taiwan.11

Egyptian opinion of American democracy remains mixed; although favorable attitudes toward the U.S. have increased by 11% this past year. The majority of Egyptians like – and only 15% dislike – American ideas about democracy. However, only 40% have a favorable opinion of the U.S. more generally (40% are neutral, and 20% have an unfavorable opinion).

Even though Egyptian opinion of American-style democracy is positive, we wanted to know what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive to everyday Egyptians. Asked to rank the top three options among a list of ten, the most popular were: the narrowing income gap between rich and poor people, less corruption in politics, and a more restrained approach to U.S. foreign policy.

In 2019, less than half (47%) of Egyptian respondents said they believe America’s democracy sets a positive example for the world. In 2020, that increased to two-thirds (66%). Egyptian belief in the power of America’s example has gone up. The increasingly positive views Egyptians have toward American-style democracy are illuminated by another finding: when asked which of a long list of countries has the best form of government, Egyptians’ top choice was the U.S.

Egyptian support for America’s style of governance is complicated by dissatisfaction with American foreign policy in and around Egypt. For instance, the belief that the U.S. should focus on the flaws of its own political system (instead of focusing on the political system of other countries) remains high at 67% over the past two years. Additionally, when asked whether Egyptians consider U.S. influence in their region/country as positive or negative, opinions were mixed. Their responses are roughly split among positive, negative, and neutral opinions toward U.S. influence.

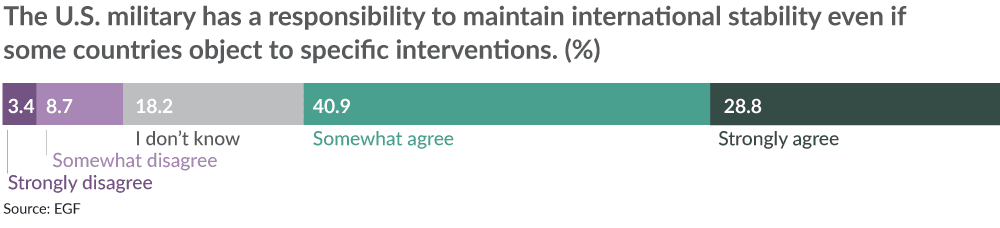

This is interesting given the history of U.S.-Egypt relations. The two countries have long enjoyed strong security ties. Over the past 30 years, the U.S. has sent around $80 billion in military and economic assistance to Egypt.12 And while a majority of Egyptians agree that the U.S. military has a responsibility to maintain international stability even if some countries object to specific interventions, and more Egyptians think the U.S. has used its use its influence for good than those who don’t, Egyptians are conflicted about whether the U.S. military’s involvement in their region of the world has effectively promoted stability.

Probing further, a plurality of Egyptians view various types of foreign influence as largely negative. This includes American military influence, foreign aid, globalization more generally, “hostile foreign influence,” and even the presence of U.S. military bases in or around Egypt.

When asked whether having China or the U.S. as the world’s leading power would be better for my country, around three-quarters of respondents favored the U.S. The primary reason why the remaining quarter of Egyptians favored China was that “China does not interfere in the politics of my country.”

Germans are proud of their form of government, and, for the second year in a row, when asked to choose which of 15 countries had the best form of government, Germany topped the list. The U.S. was not even among the top four.

People in Germany, more than any other country surveyed, hold an unfavorable view of American ideas of democracy and of the U.S. more generally. Nearly half of Germans surveyed dislike American ideas of democracy. Even China and Russia have fewer respondents in this category. Nearly 60% of Germans who dislike American-style democracy do so because “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” And, roughly half of German respondents report unfavorable views toward the U.S. (30% were neutral and fewer than 25% were favorable). More than twice as many Germans want to see their government less rather than more like the American system of government.

Negative views of the U.S. likely stem from opposition to President Trump. When asked to rank from a menu of ten things which would make “America’s style of democracy… more attractive in my country,” the overwhelming first choice was if a different person was president. However, it appears their negative opinions go beyond America’s president. When asked what they dislike most about U.S. style elections, half of Germans surveyed chose the role of money in U.S. elections.

Twice as many Germans believe the U.S. has used its influence over the past twenty years to make the world a worse, rather than a better, place. And, we found the belief that the U.S. military has effectively promoted stability around the globe decreased slightly between 2019 and 2020.

Since claims are often made that globalization benefits some countries more than others, we were curious how Germans felt about the effects of a globalized economy. We found diverse opinions among those surveyed. Interestingly, about half of Germans believe globalization has benefited Germany, but only around one-third believe it has benefitted to some degree themselves, their family, or municipality.

Looking into preferences between a China-led or a U.S.-led world order, 22% of Germans favor China and 78% favor the U.S. It will be interesting to see whether Germany’s new chancellor and its changing economic relationship with China changes how German citizens view China’s global role.13

Given the rise of far-right nationalist parties in Germany, and the influx of immigrants and refugees from the Middle East, it is notable that a strong majority of people in Germany seek to restrict immigration of certain religious groups. This is interesting since majorities are not illiberal in other ways.

India is the world’s largest democracy and, of the countries surveyed, has the most favorable views of the U.S. and America’s style of democracy. An overwhelming majority (84%) hold positive opinions about American- style democracy. (Egypt, Poland, Nigeria, and Brazil rank highly among countries who have favorable opinions of the U.S., too). Similarly, nearly 80% of those surveyed have a favorable opinion of the U.S. And just as many view U.S. influence in and around India positively. Among those who like American ideas of democracy, a plurality of respondents cite the protection of individual liberties as their primary rationale, followed by “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state.”

As in Germany, people in India take pride in their form of government. They ranked America’s form of government as the best, and India’s as second best. The U.K., of which India was once a colony, ranked third.

Among the small percentage of people in India who dislike American ideas of democracy, the most popular rationale is: “when the majority rules, the opinions of political minorities are disregarded.” This isn’t surprising given India’s historical attempts – sometimes unsuccessful – to fully accommodate its many different minority groups.

Nearly 80% of all Indians surveyed would like to see their system of government more like that of the U.S., indicating an overwhelmingly positive perception of the U.S. and American democracy. Out of a list of ten options, respondents in India ranked the following three components of democracy as the most important: equality under law, protection of individual liberties, and the freedom to vote and run for political office.

Indians also view U.S. influence in their country and region overwhelmingly positively. Around 80% of respondents believe the U.S. has made a positive impact in and around India. Additionally, unlike other countries we surveyed, all types of American influence are viewed positively, including military, economic, cultural, and political influence. This is interesting given India’s history of imperialism and foreign influence.

On the question of globalization and its benefits, an overwhelming majority of Indians feel that globalization has benefited them, their family, their municipality, and their country (over 80%). However, majorities in India also feel like globalization and other influences like foreign aid and U.S. military bases in or around India threaten India’s independence.

Only 4% think China would be better for the world than the U.S. as a leading power. This is likely attributable in part to India’s shared – and contested – border with China, and the two countries’ historically hostile relationship. And, despite a strong commitment to democracy in India, majorities prioritize security and social order above civil liberties and individual rights.

Most Japanese we surveyed continue to hold a “neutral” opinion of American ideas of democracy (60%), and there are nearly three times as many who dislike than like them. Of the ten countries surveyed, Japan has the smallest percentage of people who like American ideas of democracy (11%).

When it comes to views of the U.S. more generally, the majority remain mostly neutral (54%), although slightly more people have unfavorable views than favorable ones (26% and 20% respectively). And these views remain consistent when applied to the American people (majority are neutral at 65%, the remaining are split evenly among favorable and unfavorable views). This could be explained, in part, by the fact that a plurality of people in Japan report little interaction with American people, less travel to the U.S., and consume few American products.

The most popular rationale for why people in Japan dislike American ideas of democracy is: “when the majority rules, the opinions of political minorities are disregarded.” This is interesting, but not unsurprising given their system of government is a multiparty parliamentary democracy in which the Japanese take great pride. They rank Japan as the best system of government out of 15 different countries. The U.S. comes in second. Most want their system of government to be neither more nor less like that of the U.S. (47%) and a greater number of respondents want their system of government to be less rather than more like that of the U.S.

Respondents in Japan are generally indifferent to American foreign policy. When asked whether the U.S. has had a positive or negative influence on the world over the past twenty years, around half of the population surveyed feels American influence has made little or no difference with a quarter saying it’s been somewhat positive, and around a quarter saying it’s been somewhat negative.

When asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive in Japan, the top answer choices were: if America’s news media was less focused on scandal and superficial things, if the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained, and if the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller.

Lastly, and unsurprisingly given Japan’s geopolitical standing, people in Japan strongly oppose having China as the world’s leading power. Like India, only about 4% prefers China. The number one reason people prefer the U.S. to China is because “my country has a history of working closely with the United States.” This is followed by: “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner.”

A country with close cultural and economic ties, and geographic proximity, Mexico does not have particularly favorable opinions of the U.S. and its style of democracy, and comes close to favoring a China-led world. While other countries we surveyed hold unfavorable views of the U.S., most people nevertheless support American-style democracy and think the U.S. has the best form of government.

Not so for Mexico. Mexicans selected Canada and Germany above the U.S. as the countries with the best system of government. People in Mexico value the same attributes of democracy that others around the world value (i.e. equality under the law and the protection of individual and civil liberties), but they are divided over how they feel those ideas play out in America. Mexican respondents are evenly split between liking, disliking, and having a neutral view about American ideas of democracy. The most frequent response to why they dislike these ideas is: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive, the most popular answer choices were: if minority groups were treated more fairly, if there was less corruption in politics, and if the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller.

The most frequent answer for what people dislike most about U.S. elections was the role of money in U.S. elections followed by the level of corruption in U.S. elections.

Additionally, a plurality of Mexicans want their government’s relationship with the U.S. to either remain the same or opposed to the U.S. Only 10% of respondents want Mexico’s relationship to be much more supportive of the U.S.

Forty-four percent of Mexicans surveyed have either somewhat favorable or very favorable opinions of the U.S. but more than one-third of respondents have unfavorable views, and one-quarter reported neutral opinions. Even though people in Mexico are more skeptical about American ideas of democracy, a plurality wants to see their system of government become somewhat more like that of the U.S.

Mexican views about American foreign policy are also conflicting. More believe U.S. influence has been negative than positive, with around 20% indicating U.S. influence has made little or no difference in and around Mexico.

Around 50% of Mexicans surveyed believe “the sale of American military weapons and vehicles to my country’s military” has been either very negative or somewhat negative. This is intriguing given America’s focus on providing security assistance to Mexico to combat crime and corruption.14 While roughly half report the U.S. has a “responsibility to protect vulnerable groups of people even if it requires armed intervention,” they are divided over whether the U.S. military’s involvement in their region has effectively promoted stability. Slightly more than half believe it has not.

More than half of respondents believe “the presence of U.S. military bases in or around my country threatens the independence of my country.” People in Mexico do not harbor as much animosity toward other influences like foreign aid or globalization, but do feel as strongly about the threat of “hostile foreign influence.”

Globalization, however, does not seem to be perceived as having benefited Mexico in the way that it has other emerging economies. Brazil, India, and Nigeria report more favorable views of globalization. A plurality somewhat agree that globalization has benefited them, their family, city, and country. But about one-third either strongly disagree or somewhat disagree.

Like Russians, Mexicans are torn about whether China or the U.S. would be better as the world’s leading power. The top reasons why people in Mexico favor China over the U.S. are: “China sets a good example for national development for my country,” and “China does not interfere in the politics of my country.” The most popular rationale for respondents who favor the U.S. as the leading power chose: “my country has a history of working closely with the United States” and “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner.”

After three decades of military rule, Nigeria regained democracy in 1999. The youngest democracy among the countries we surveyed, Nigeria continues to be home to one of the most pro-American publics among the ten countries under study.

Around the same time we fielded this survey, President Trump extended travel restrictions to six additional countries, including Nigeria. People from the country will only be allowed to settle in the U.S. temporarily. Did this new law affect Nigeria’s overwhelmingly positive views of the U.S.? While we did not see an increase in negative views toward the U.S., there was a noticeable decrease in positive views among Nigerians. Between 2019 and 2020, there was a 7% decrease in very favorable views, a 2% decrease in somewhat favorable views, and a 13% increase in people who had a neutral opinion of the U.S.

Despite an increase in neutral opinions of the U.S., Nigeria continues to rank highly among the countries surveyed who like American ideas of democracy. The majority of the population (75%) likes American ideas of democracy. The most popular reasons why they like American ideas of democracy are: “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion) is important” and “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state.” A majority of Nigerian respondents have a favorable view of the U.S. more generally, with fewer than 10% reporting unfavorable views. And among all of the countries we surveyed, Nigeria has the fewest who look upon the U.S. negatively. The majority of Nigerians believe the U.S. has used its influence over the past twenty years to make the world a better place.

While Nigerians have a particular fondness for America’s system of governance, they appear to have a particular dissatisfaction with their own. The countries Nigerians thought had the best form of government were: the U.S., U.K., Canada, Germany, and then China. Nigeria itself ranked very low on this list. People prefer Russia’s system of government to their own.

Corruption is top of the mind for people in Nigeria which is unsurprising given political corruption remains pervasive despite improvements in its election systems.15 When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive, the most popular answer choice was if in the U.S., “there was less corruption in politics.” This was followed by if “the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller” and if “minority groups were treated more fairly.” They place a special focus on the rights of minorities, as supported by our finding that shows the majority of Nigerians believe their government should “take into account the interests of the political minority, even if it means the political majority does not get what it wants.”

With respect to American influence in Nigeria, 75% reported U.S. influence in and around Nigeria has been positive (less than 7% report negative). Most types of influence, including America’s diplomatic, military, and economic presence, is viewed positively.

The majority of Nigerians surveyed report globalization has benefited them, their family, municipality, and country. And, more people disagree, than agree, that foreign influences like foreign aid, globalization, and even the presence of the U.S. military bases in and around their country threatens their independence. The majority view these foreign (and American) influences positively.

A large number of Nigerians consume American movies, music, and news media and/or have family members or friends who live in the U.S., though most of the people surveyed did not report having visited or lived in the U.S.

Most think the U.S. would be better than China for the world as the leading power; though slightly fewer feel the U.S. would be better than China for their own country. China might appeal more to people in Nigeria as its investment in African countries deepens. After all, the main reason given by those who favor China is because “China can provide my country with economic investment or assistance” and “China sets a good example for national development for my country.” The reason people preferred the U.S. as the leading power is because “the United States promotes democracy and human rights around the world.”

The Polish public generally has a positive opinion of the U.S.; although favorable views decreased by 11% between 2019 and 2020 (71% to 60%).

Despite this change, Polish respondents strongly favor American-style democracy. Like India and Nigeria, the majority of Poles somewhat like or strongly like American ideas of democracy (65%). And, for the second year in a row, Poles reported the most important elements of a democratic system are equality under the law and the protection of individual liberties. Democracy is likely top of mind for Poles amid President Andrzej Duda’s new laws forbidding judges from questioning judicial appointments, and other undemocratic reforms to the Polish court system.16

When asked what most contributes to you liking American ideas of democracy, a plurality (40%) chose “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion).” Nearly three-quarters of Poles (71%) indicated their system of government should be somewhat or much more like that of the U.S.

A majority think the U.S. has used its influence to make the world somewhat or much better over the past twenty years. Even America’s military footprint in and around Poland is viewed positively: Seventy-five percent believe the military collaboration between the U.S. and Poland is positive (while only 8% view it negatively). Countries like Poland and India stand out among countries who view this kind of influence positively (India is at 82%). Other countries are more negative in their assessment of America’s military impact, in particular. In fact, American military influence is viewed as positively as other sources of American influence in Poland, such as the presence of U.S. embassies and diplomats, economic aid, and investment by private companies.

With respect to America’s role globally, over 85% of Polish respondents believe the U.S. has a responsibility to maintain international stability. They similarly feel that the U.S. has a responsibility to protect vulnerable populations, even if that requires armed intervention. This makes sense since the vast majority agree that the U.S. has effectively promoted stability around the world.

Given how highly Poles think of America and having a better understanding of the potential reasons why it is not surprising they would overwhelmingly favor a U.S.-led world order to one led by China (only 5% chose China when asked which country they would rather have as the world’s leading power).

Another finding which complicates Poland’s affinity for liberal democracy, but foreseeable with the rise of Islamophobia and the power of right-wing parties, is that Poles tend to favor liberal values in the face of instability but not when it comes to restricting immigration of certain religious groups. In fact, a strong majority (70%) believe “laws should be able to restrict immigration of certain religious groups into my country if those groups jeopardize national unity.”

Do Russians view the U.S. and America’s system of government favorably? Our findings suggest that America’s foreign policy stands in the way.

Asked to rank the top three countries with the best form of government, Russian respondents ranked the most popular choices (in order): Russia, Germany, China, and Japan. Only then came the U.S. and the UK. When asked whether they had a favorable or unfavorable opinion of the U.S., like Mexico, their answers were mixed: nearly 40% had a neutral view, while around 25% had unfavorable views, and 35% had favor- able ones. Views of the American people, however, were more positive: only 5% report having unfavorable views of the American people. Favorable views toward the American people might be explained by the fact that a majority of Russians frequently consume American movies and music (though only a handful of respondents report having family or friends who live or have lived in the U.S.).

After Germany, Russia had the largest number of people who said they strongly dislike American ideas of democracy – only 8% of them said they strongly like these ideas. A reason that might explain these unfavorable views is: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypothetical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power” – which nearly 75% chose as their rationale for why they dislike American ideas of democracy.

Respondents in Russia are more uniform in their opinions when it comes to American influence and foreign policy. A majority indicated U.S. influence over the past twenty years has made the world a worse, as opposed to a better, place. Fifty percent report U.S. influence in and around Russia has been either somewhat negative or very negative. Interestingly, the type of American influence viewed most negatively is not security-related, as might have been expected. Rather, a majority of Russians view the “importation of Western education models” negatively, and “the presence of the U.S. government to support the development of my country” negatively. Yet, nearly 70% view the import of American consumer products (e.g., clothing or technology) positively.

Our findings suggest a shift in American foreign policy might affect favorable views of American democracy. When asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive in Russia, the most popular answer was: “if the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained.” We also found that 60% of Russian respondents favor China as the world’s leading power: only 40% favor a U.S.-led order. The preference for China over the U.S. is even more pronounced when asked which leading power would be better for Russia, specifically, not more generally “the world.” And, the reasons they favor China over the U.S. are illuminating: “my country has a history of working closely with China” and “China does not interfere in the politics of my country.” Those who chose the U.S. over China gave the reason that “the U.S. is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner” and “the United States values individual freedoms more than other countries do.”

An interest in China over the U.S. also makes sense in the context of Russian opinion of civil liberties versus stability and unity. Even though Russians value democratic attributes (e.g., the most important attributes of democracy for them are equality under the law and the protection of individual freedom), it seems that stability is more important. For instance, when asked if political protest should be blocked, a majority of Russians believe those protests should be blocked if they disrupt the social order.

The silver lining? Although a plurality of Russians wish the U.S.-Russia relationship remains as it is currently, our findings show that more Russians want to see their government have a better, as opposed to a worse, relationship with the U.S.

Conclusion

One of the primary objectives of the Eurasia Group Foundation’s Independent America project, of which this report is a part, is to better understand the possibilities and benefits of a less militarized U.S. foreign policy. Even though this is principally a comparative study of international public opinion toward the U.S. and American-style democracy, we designed this survey instrument to include questions which would help us learn about people’s views on such matters as America’s military might, security cooperation, arms sales, and its forward deployed presence.

It’s a good thing we did. While most people in the ten countries we surveyed appraise the U.S. and its form of government positively, America’s expansive and interventionist foreign policy drives a lot of negative opinion. We expected people in China and Russia to wish for a U.S. foreign policy that was more restrained, and indeed in both countries that topped the list of ten things which would make American democracy more attractive. But it was also one of the top three choices for U.S. allies like Germany and Egypt (the latter of which has received more than $80 billion in military and economic aid in the past 30 years, and and otherwise saw an uptick in positive views of the U.S. in the past year).

Moreover, across all the countries surveyed, people who seek a more restrained U.S. foreign policy are significantly more likely to have a negative view of the U.S. The only other answer option with such a relationship was wanting a different person as the American president. And of the ten different types of assistance we listed, among the least popular were the “U.S. military’s collaboration with my country” and “the sale of American military weapons and vehicles to my country’s military.”

In last year’s report, the positive views of the U.S. from survey respondents in China came as a surprise to many. Most wanted to see their country’s political system become more like America’s. This year, not so much. Between 2019 and 2020 in China, positive opinions about the U.S. fell by 20% and positive opinions of American ideas of democracy decreased by 15%. Even positive views of the American people went down.

Last year, a slight majority of Chinese wanted their government to be either somewhat or much more like that of the U.S. This year, that dropped to about a quarter. It’s likely this declining support for America is attributable in part to the Trump administration’s trade war, and to America’s vocal support for pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong.

We call out the changing opinion in China here not only because that change is so stark, but because the geopolitical stakes of America’s relationship with China are so high. The Trump administration’s response to the coronavirus pandemic – whether it sets a tone of cooperation and mutual aid or of criticism and blame – will likely influence the trajectory of this trendline in next year’s report.

Perhaps more critical than opinion within China is opinion about China for those who formulate American foreign policy. This is especially important to understand now that China seizes on the COVID-19 outbreak as an opportunity to demonstrate its standing as a new superpower. China appears to be trying to step into global leadership roles formerly filled by the U.S., including by organizing an international response to the virus through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and “17 + 1” group of Eastern European nations, and by sending shipments of aid to hard-hit nations. Given China’s increasing international influence, it will be interesting to gauge whether and why foreign publics perceive China as a more desirable hegemony than the U.S. We have some benchmark data, having asked for the first time whether respondents think China or the U.S. as “the world’s leading power” would be better for their country.

Of a list of rationales for picking the U.S. over China, the two most frequent responses relate to economic partnership, and a history of working closely with the United States. Less frequently selected reasons relate to democracy, freedom, and human rights. Conversely, economic partnership and a history of working closely with China were, in fact, the least frequently selected response categories for those who prefer China. People who choose China did so because it “values…stability over individual freedoms” and because it “does not interfere” in their country’s politics.

In short, while there is still a strong preference for U.S. leadership, this preference is fueled more by pragmatic assessment of national interest than many in Washington might presume. And people who chose China did so, arguably, based on perceptions rather than experiences with China. It’s conceivable that, as China expands its economic partnership with other countries, and develops a legacy of working cooperatively with other countries, popular support for its global leadership will increase. Moreover, America’s awed response to the coronavirus pandemic could diminish confidence in its continued global leadership, potentially creating an opening for China to claim an elevated role on the world stage.

This brings us to the question of how international public opinion informs foreign policy making, or at least why it should. The State Department invests heavily in public diplomacy efforts designed to sway proverbial hearts and minds, around $2 billion annually.17 This is predicated on the understanding that, even in nondemocracies, popular opinion enables and constrains the actions of foreign leaders. But as our research shows, some of the most effective ways of influencing positive views of the U.S. are tied to immigration and trade policy. People throughout the world are more likely to have a favorable opinion of the United States if they have a close friend or family member living here, have visited recently, or if they consume American cultural products.

Pundits often say we are stronger for being a nation of immigrants. They are typically correct not only in the way they mean – that a diversity of cultures and experiences enriches American civic life – but in a way they don’t: America’s historically hospitable approach to immigration is a significant source of its soft power, generating public goodwill which helps it collaborate with and put pressure on foreign governments.

As America’s hard power provokes resentment, so its soft power prompts pro-Americanism abroad. This might seem intuitive to some, but we hope our study makes a modest contribution to demonstrating this distinction empirically. These findings have all kinds of policy implications. The Trump administration’s travel ban is likely to reduce legal immigration and tourism from precisely the countries where the United States could use an uptick in positive sentiment. Its trade war with China threatens to reduce the prevalence of American movies and news outlets available to Chinese consumers. And the belligerence toward Iran, resumption of military aid to Egypt, and the sale of large amounts of military weapons and vehicles to Saudi Arabia are likely to trigger more anti-American opinion around the world.

To be sure, while American national security and foreign policy should be attentive to public opinion around the globe, it shouldn’t be overdetermined by it. Sometimes, leaders should act – or not act – in ways which might make them and their country internationally less popular. But when they do, they should be straightforward with their citizens, to whom they are ultimately accountable, about the costs of that reputational damage, and about the national interests being nevertheless advanced. After all, many national interests – from securing allies and trading partners to promoting democracy and human rights – are promoted by attracting the support of public opinion abroad. So as we continue to conduct this international survey, we hope our findings will inform policymakers and opinion leaders in their deliberations and decisions.

Methodology

This survey was developed and commissioned by EGF. The survey instrument was written by Mark Hannah with the help of two research assistants18 in 2019 and was updated for 2020 by Caroline Gray and Mark Hannah. The survey was distributed online by Qulatrics, a large, commercial survey company to a geographically and demographically diverse sample of 5,249 adults. This included a sample of approximately 730 respondents in China and India, and 470 respondents in each of the other eight countries. The survey was distributed between February 15 and March 3, 2020. Events during the period of time the survey was fielded, such as U.S. President Donald Trump’s official visit to India or his administration’s extended travel ban to include Nigeria, may have affected responses in India and Nigeria, respectively. Two countries, Mexico and Russia, were added to this year’s survey. Our survey partner created quotas to ensure gender and age balance, especially in certain countries where older respondents were scarce (e.g. Nigeria and Poland). The representativeness of this sample and margin of error, of course, vary with the population size of each country. For example, our results from China and India have a larger margin of error than those from Germany or Egypt.

We commissioned professional translators to translate the survey into the dominant language in each country and offered our survey respondents the option to complete the survey in that language or English. We did not translate the survey into other regional languages and dialects (e.g., Bengali in India or Cantonese in China).

Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized.

Establishing statistical significance in the relationship between questions, we used an ordered logistic regression when the dependent variable came from one of our Likert scale questions (e.g, “very unfavorable” to “very favorable”) and a simple linear regression when analyzing continuous data (e.g., birth year or age).

The question about “American ideas of democracy” was taken from a Pew Global Attitudes Project survey in consultation with a senior member of the research staff there. Depending on the user’s response to that question, we used a skip logic function to pose a follow-up question seeking reasons for “liking” or “disliking” American ideas of democracy. This same skip logic function was used for the question “Having ____ as the world’s leading power would be better for my country.” Depending on the user’s response to that question, we sought reasons for selecting either “China” or “The United States.”

About the Authors

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.)

Caroline Gray is a research associate at EGF. She previously worked on the policy team of the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.

Endnotes

1. David Wallace-Wells, “America is Broken.” Intelligencer, March 12, 2020. Retrieved from: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/03/coronavirus-shows-us-america-is-broken.html?fbclid=IwAR0Mhkv7Z1KkXeA_sYhJdE7aJP62PAxFKNfKs0oP4OUWjCnmUj45ghq0sZ8.

2. “2020 Edelman Trust Barometer Special Report: Trust and the Coronavirus,” (March 2020). Edelman. Retrieved from: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2020-03/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Coronavirus%20Special%20Report_0.pdf.

3. Ian Bremmer, “Who is doing the best job responding to Coronavirus crisis?” (March 14, 2010). Twitter. Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/ianbremmer/status/1238927709386027008.

4. These answer options revealed a statistically significant relationship at P < 1%.

5. Numbers reflect the percentage of people in a given country who chose the answer option as their first choice.

6.This list uses a weighting scheme so all three of the respondents’ selections are included – first choices are weighed more heavily than second choices, etc. Note that Germans, Japanese, Chinese, and Russians were among the countries surveyed.

7. A 2010 Pew Global Attitudes and Trends survey shows that a majority of Brazilians are concerned about things like income inequality, corruption, minority rights and climate change within the context of their own society: 79% view “corrupt political leaders” as a “very big problem” in Brazil; 66% view “social inequality” as a “very big problem;” and, according to Pew: “Brazilians express more concern about global climate change than any public surveyed; 85% say it is a very serious problem. Moreover, eight-in-ten say protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it results in slower economic growth and loss of jobs.” “Brazilians Upbeat About Their Country, Despite Its Problems” (2010). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2010/09/22/brazilians-upbeat-about-their-country-despite-its-problems/.

8. See: “Before Venezuela, US Had Long Involvement In Latin America.” Associated Press, January 25, 2019. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/2ded14659982426c9b2552827734be83 and Kenneth P. Serbin, “The Ghosts of Brazil’s Military Dictatorship: How a Politics of Forgetting Led to Bolsonaro’s Rise.” Foreign Affairs, January 1, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/brazil/2019-01-01/ghosts-brazils-military-dictatorship.

9. “On The Ideological Right, Confidence In Trump Has Increased In Many Nations” (2020). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/01/08/trump-ratings-remain-low-around-globe-while-views-of-u-s-stay-mostly-favorable/pg_2020-01-08_us-image_0-04/.

10. See: “China Expels U.S. Journalists In Biggest Crackdown In Years.” Japan Times, March 18, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/03/18/asia-paci%20c/china-us-journalists-media-crackdown/#.Xnq_15NKj_Q and “China Imposes ‘Reciprocal’ Restrictions On US Diplomats.” Straits Times, December 6, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/china-imposes-reciprocal-restrictions-on-us-diplomats.

11. Chris Horton, “Taiwan Set to Receive $2 Billion in U.S. Arms, Drawing Ire From China.” New York Times, July 9, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/09/world/asia/taiwan-arms-sales.html.

12. See: The Associated Press, “US Acts to Release $195M In Suspended Military Aid to Egypt.” Defense News, July 25, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.defensenews.com/global/mideast-africa/2018/07/25/us-acts-to-release-195m-in-suspended-military-aid-to-egypt/.

13. Noah Barkin, “Get Ready for Merkel’s Pro-Russia, China-Friendly Successor.” Foreign Policy, March 9, 2020. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/09/armin-laschet-merkels-pro-russia-china-friendly-successor/.

14. Learn more about America’s security assistance to Mexico: Congressional Research Service. Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, 2007-2020. Updated February 19, 2020. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10578.pdf.

15. Abbas Umar, “Corruption and Nigeria’s Image.” The Punch, March 10, 2020. Retrieved from: https://punchng.com/corruption-and-nigerias-image/.

16. The Associated Press Staff, “In Poland, Controversial Legislation Restricting Judiciary Is Signed Into Law.” The New York Times, January 4, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/04/world/europe/Poland-judiciary-law.html.

17. In fiscal year 2018, the U.S. government spent 2.19 billion dollars for public diplomacy efforts which is “3.9 percent of the 2018 international affairs budget or 0.17 percent of federal discretionary spending.” See: “Comprehensive Annual Report On Public Diplomacy & International Broadcasting: Focus on FY 2018 Budget Data” (2019). United States Advisory Commission On Public Diplomacy. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2019-ACPD-Annual-Report.pdf.

18. The authors acknowledge the skillful assistance of EGF’s talented interns in the development and execution of this survey and report. From Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, Steve Maroti valuably assisted with the data analysis, and Clara Brackbill contributed valuable research assistance. Keenan Ashbrook of Cornell University and Cartland Zhou of New York University valuably assisted in developing the original survey instrument in the summer of 2018.

This post is part of Independent America, a research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.